Recipe for Serving Thousands of Concurrent LoRA Adapters

by: Ying Sheng*, Shiyi Cao*, Dacheng Li, Coleman Hooper, Nicholas Lee, Shuo Yang, Christopher Chou, Banghua Zhu, Lianmin Zheng, Kurt Keutzer, Joseph E. Gonzalez, Ion Stoica, Nov 15, 2023

In this blog post, we introduce S-LoRA (code), a system designed for the scalable serving of many LoRA adapters. S-LoRA adopts the idea of

- Unified Paging for KV cache and adapter weights to reduce memory fragmentation.

- Heterogeneous Batching of LoRA computation with different ranks leveraging optimized custom CUDA kernels which are aligned with the memory pool design.

- S-LoRA TP to ensure effective parallelization across multiple GPUs, incurring minimal communication cost for the added LoRA computation compared to that of the base model.

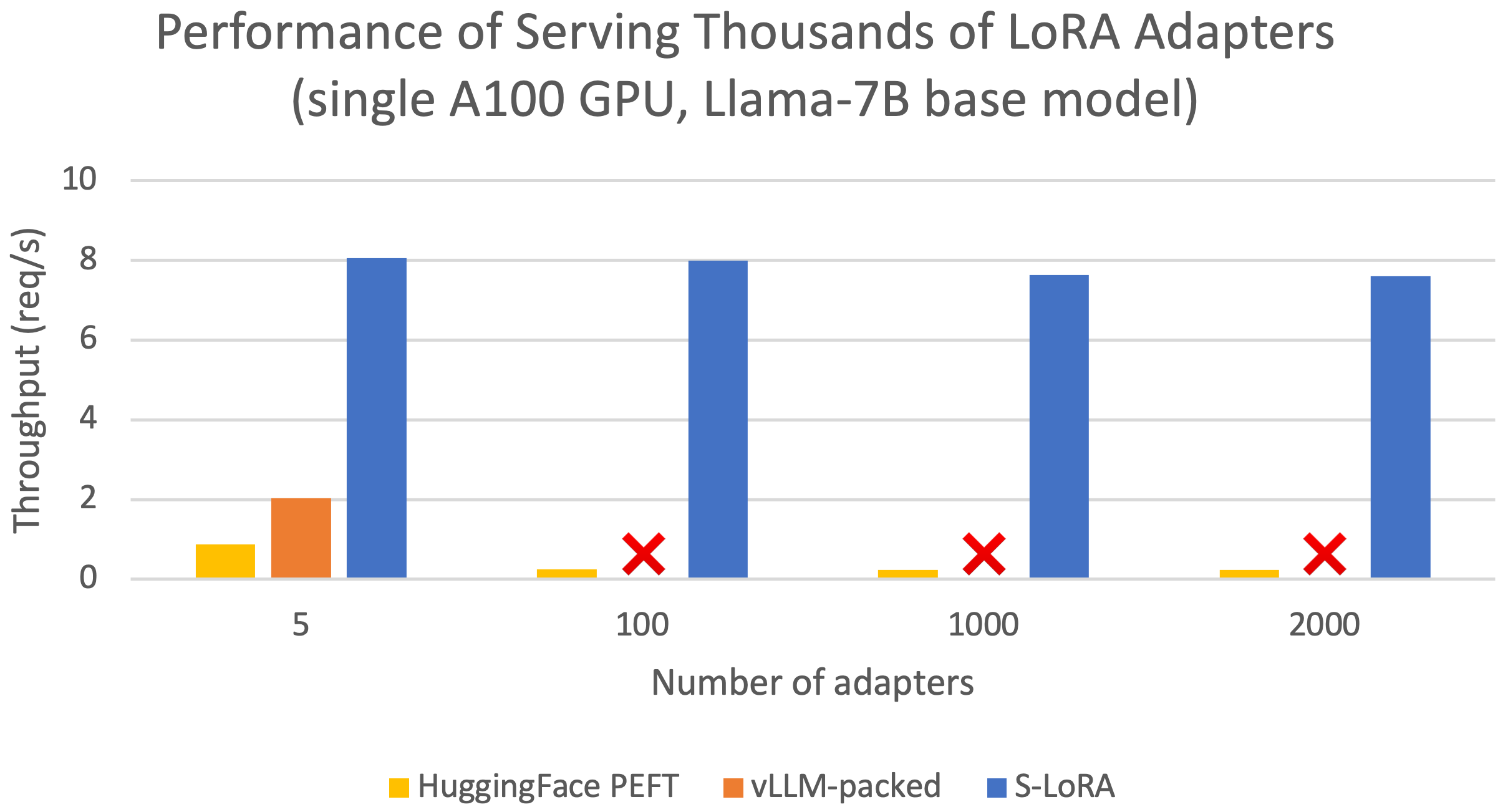

Evaluation results show that S-LoRA improves the throughput by up to 4 times and increase the number of served adapters by several orders of magnitude compared to state-of-the-art libraries such as HuggingFace PEFT and vLLM (with naive support of LoRA serving).

Figure 1: Performance comparison between S-LoRA, vLLM-packed, and PEFT.

Introduction

The "pretrain-then-finetune" paradigm is commonly adopted in the deployment of large language models. Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA), a parameter-efficient fine-tuning method, is often employed to adapt a base model to a multitude of tasks, resulting in a substantial collection of LoRA adapters derived from one base model. Scalable serving of these many task-specific fine-tuned models is of crucial importance and offers the potential for large-scale customized LLM services. Below we briefly introduce how LoRA works and discuss about several of the design choices we met in practice for scalable serving of many concurrent LoRA adapters.

Low-Rank Adaption (LoRA)

The motivation behind LoRA stems from the low intrinsic dimensionality of model updates during adaptation. In the training phase, LoRA freezes the weights of a pre-trained base model and adds trainable low-rank matrices to each layer. This approach significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters and memory consumption. When compared to full parameter fine-tuning, LoRA can often reduce the number of trainable parameters by orders of magnitude (e.g., 10000×) while retaining comparable accuracy.

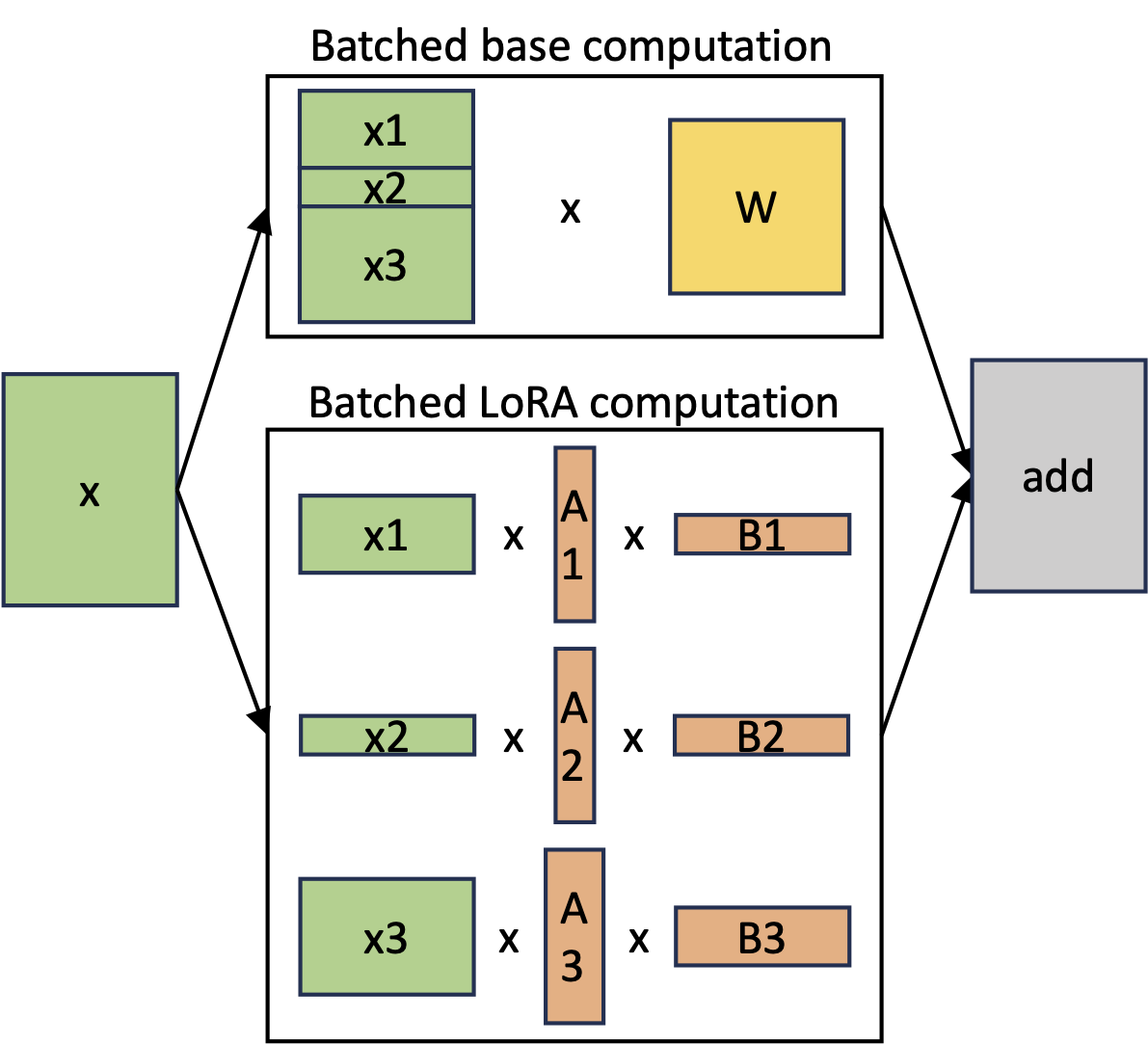

Formally, for a pre-trained weight matrix $W\in \mathbb{R}^{h\times d}$, LoRA introduces the updates as $W' = W + AB$, where $A\in \mathbb{R}^{h\times r}$, $B\in \mathbb{R}^{r\times d}$, and the rank $r \ll \min(h,d)$. If the forward pass of a base model is defined by $h=xW$, then after applying LoRA, the forward pass becomes $h = xW' = x(W+AB)$ (Eq.(1)), and we then have $h = xW + xAB$ (Eq.(2)).

x(W + AB) v.s. xW + xAB

One of the key innovations in the LoRA paper was the elimination of adapter inference latency by directly merging the adapter with the model parameters (as suggested by Eq.(1)). Additionally, to support multiple models on a single machine, the same paper proposes swapping adapters by adding and subtracting LoRA weights from the base model. While this approach enables low-latency inference for a single adapter and serial execution across adapters, it significantly reduces overall serving throughput and increases total latency when serving multiple adapters concurrently. We observe that the shared base model, which underpins numerous LoRA adapters, presents a substantial opportunity for batched inference. To achieve high-throughput multi-adapter serving, it is advantageous to separate the batchable base model computation from individual LoRA computations (as suggested by Eq.(2)).

Figure 2: Separated batched computation for the base model and LoRA computation.

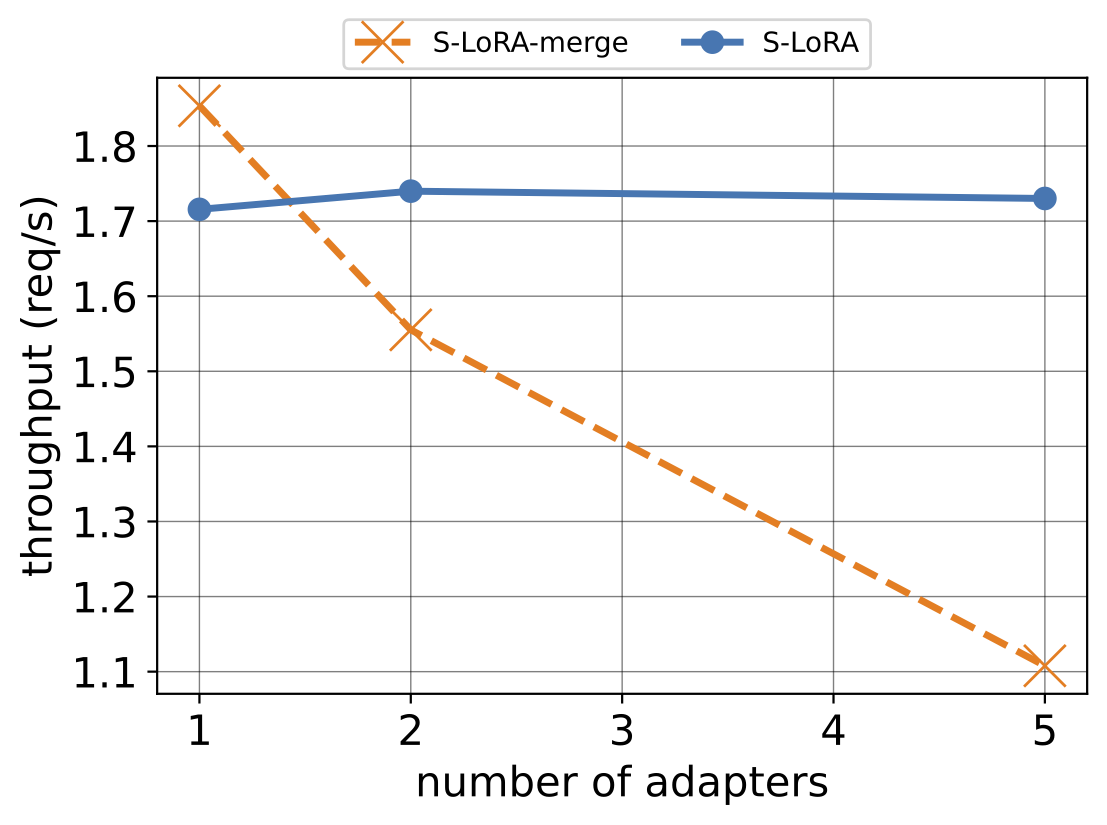

In the figure below, we demonstrate a comparison between the two ways of performing the computation. For the adapter weights merging approach, we (1) update the base model with current adapter weights before each new batch, and (2) switch to a new adapter if there are too many waiting requests. We can see from the results that the merging method is efficient when there's only one adapter, outperforming the on-the-fly computation owing to a one-time merging cost. However, its performance declines with more than 2 adapters, primarily because of the time-consuming switch between adapters. Such switching results in periods of GPU under-utilization. More adapters will lead to more frequent such switch and thus we believe that separating the computation for base model and LoRA addons should be the right choice for scalable LoRA serving.

Figure 3: Ablation study comparing adapter merging and on-the-fly compute on A10G (24GB) with different number of adapters.

Reserved Memory v.s. Unified Memory

Another thing that needs to be figured out is how we should manage the memory for the adapters on GPU. One way to do this is to reserve some memory on GPU for adapter weights and smartly swap in & out the adapters from / to the host DRAM. Such method has certain limitations:

- When the memory consumption of current active adapters is less than the reserved memory, we waste some memory that could be used for KV cache. This restriction ultimately reduces the attainable maximum batch size, leading to decreased throughput.

- On the other hand, the reserved memory size can limit the maximum number of active adapters, which may result in insufficient requests for continuous batching and thus lower throughput.

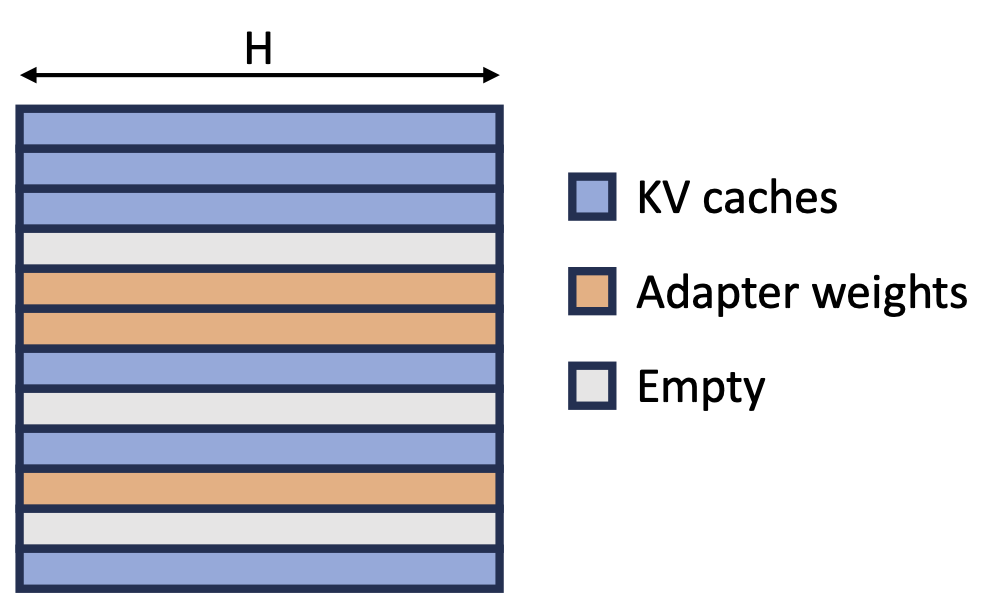

Given these factors, it is natural to consider a dynamic memory management scheme that can adjust the ratio of memory assigned to KV cache and adapter weights. A simple solution for this is to put them into the same pool and adopt the paging strategy, extending the idea of paged KV cache in vLLM.

A KV cache tensor for a request in a layer has a shape of (S, H), where S denotes the sequence length and H represents the hidden dimension of the served model. The shape of a LoRA weights is (R, H) with R standing for the rank and H the hidden dimension. Notably, both S and R varies. From here we can observe that H is a common factor of all these different object sizes. Therefore, by setting the page size to be H in the memory pool we can significantly reduce the memory fragmentation and ease the memory management on a large scale.

Non-contiguous Memory Layout

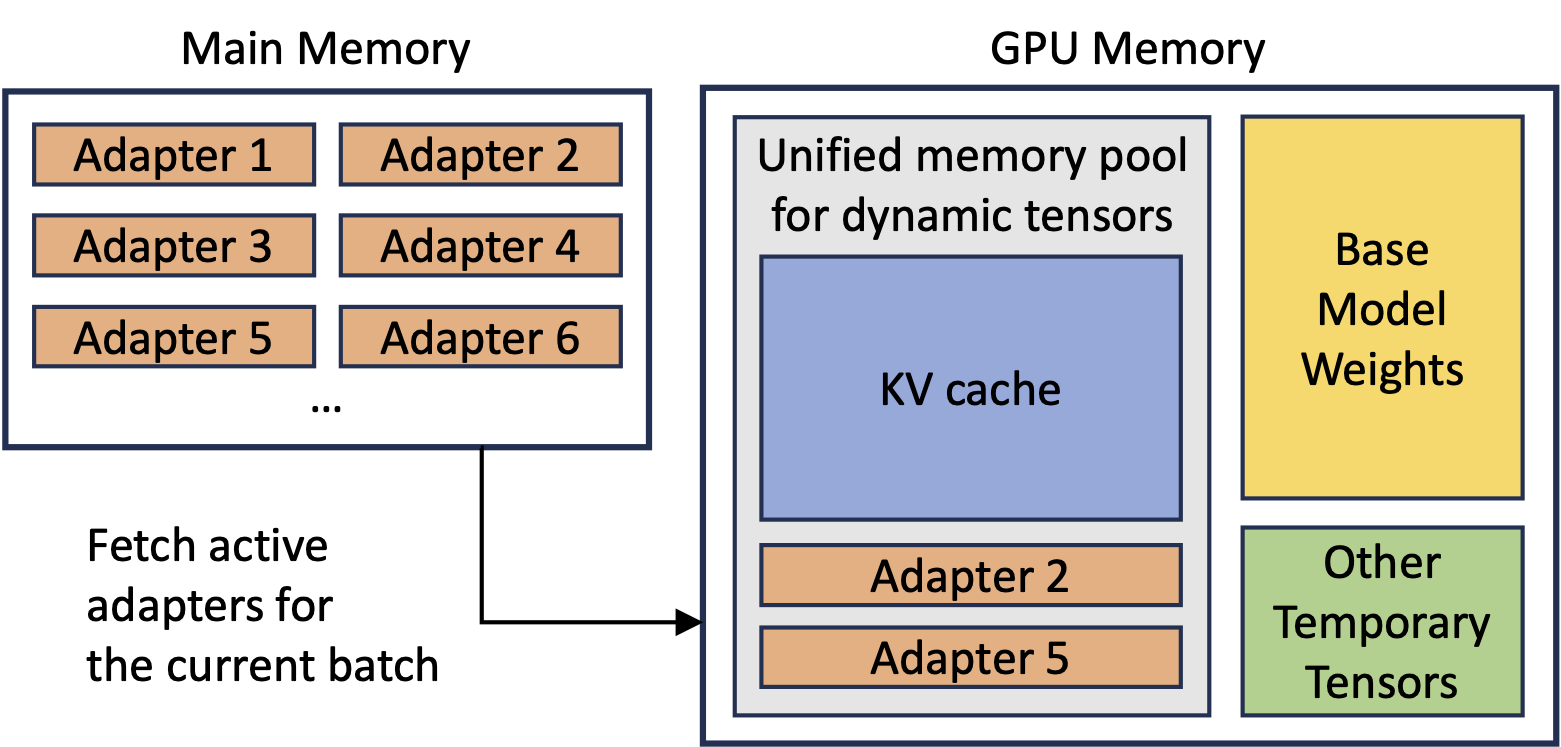

As a result of our unified memory pool, the KV caches and adapter weights are stored interleaved and non-contiguously, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 4: KV cache and Adapter Weights Layout in the Unified Memory Pool.

One challenge of non-contiguous memory layout for KV cache and adapter weights is that we cannot utilize the high-performance operators provided in popular libraries such as Pytorch and xFormers, as they all require the tensors lie in contiguous memory. For paged attention, we utilize LightLLM's implementation for TokenAttention. For paged LoRA computation, CUTLASS provides high-performance Grouped Gemm kernels, but it still requires the contiguous memory layout for each adapter's weights. Therefore we implemented customized kernels for our memory pool. In the prefill stage, for each request the kernel handles a sequence of tokens and gathers adapter weights with different ranks from the memory pool. We implemented it in Triton with tiling. In the decode stage, for each request the kernel handles a single token and gathers adapter weights with different ranks from the memory pool. It is modified from Punica's BGMV kernel to support multiple ranks in a batch and more fine-grained memory gathering, aligned with our memory pool design.

Scale Beyond one GPU - Tensor Parallelism

Tensor parallelism is the most widely used parallelism method since its single-program multiple-data pattern simplifies its implementation and integration with existing systems. Tensor parallelism can reduce the per-GPU memory usage and latency when serving large models. In our setting, the additional LoRA adapters introduce new weight matrices and matrix multiplications, which calls for new partition strategies for these added items.

The base model uses the Megatron-LM tensor parallelism strategy, our approach aims to align the partition strategies of inputs and outputs of the added LoRA computation with those of the base model. We further minimize the communication costs by avoiding unnecessary communications and fusing some of the communications.

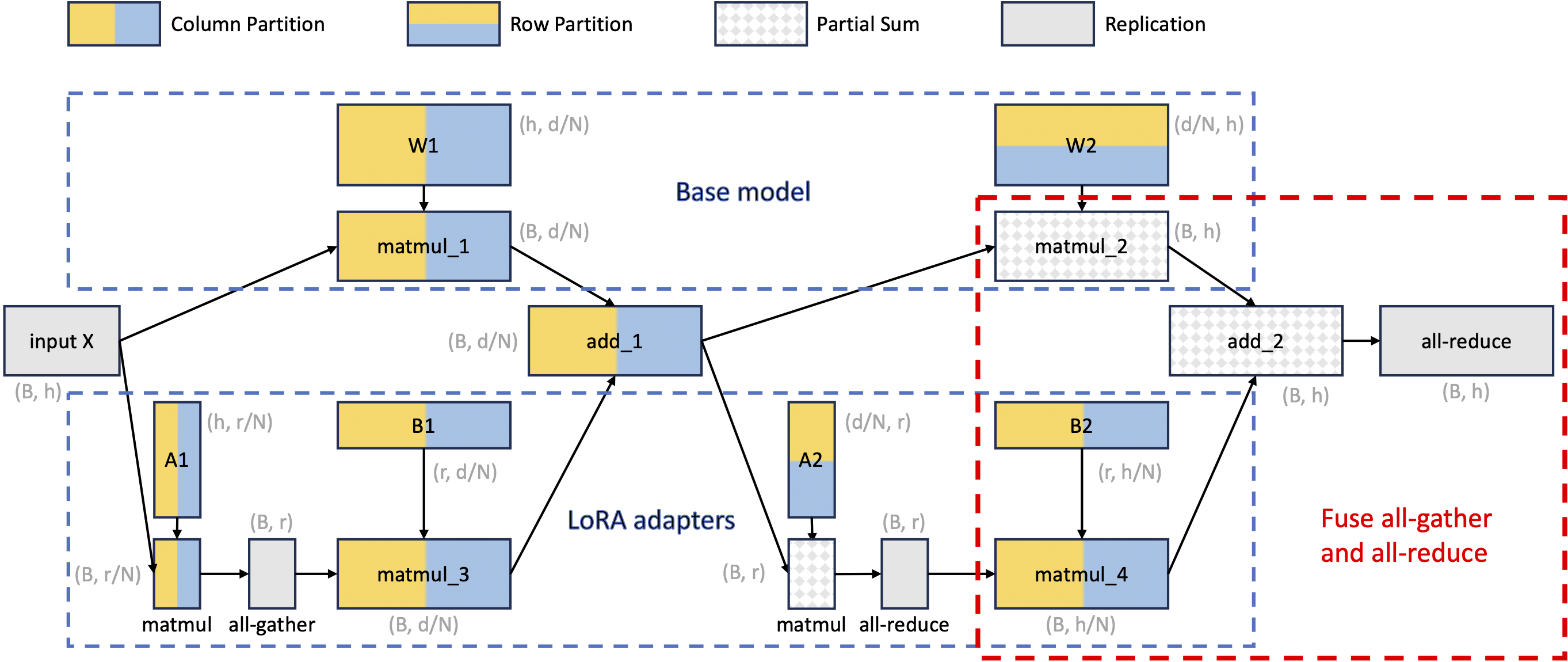

Figure 5: Tensor parallelism partition strategy for batched LoRA computation.

The figure above demonstrates the tensor parallelism partition strategy for batched LoRA computation. This is a computational graph where nodes represent tensors/operators and the edges represent dependencies. We use different colors to represent different partition strategies, which include column partition, row partition, partial sum, and replication. The per-GPU shape of each tensor is also annotated in gray. Note that $B$ is the number of tokens, $h$ is the input dimension, $N$ is the number of devices, $d$ is the hidden size, and $r$ is the adapter rank.

Methods Summary

- Unified Paging: To reduce memory fragmentation and increase batch size, S-LoRA introduces a unified memory pool. This pool manages dynamic adapter weights and KV cache tensors by a unified paging mechanism.

- Heterogeneous Batching: To minimize the latency overhead when batching different adapters of varying ranks, S-LoRA employs highly optimized custom CUDA kernels. These kernels operate directly on non-contiguous memory and align with the memory pool design, facilitating efficient batched inference for LoRA.

- S-LoRA TP: To ensure effective parallelization across multiple GPUs, S-LoRA introduces a novel tensor parallelism strategy. This approach incurs minimal communication cost for the added LoRA computation compared to that of the base model. This is realized by scheduling communications on small intermediate tensors and fusing the large ones with the communications of the base model.

Figure 6: Overview of memory allocation in S-LoRA.

Evaluation

Model Settings

| Setting | Base model | Hidden size | Adapter ranks |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Llama-7B | 4096 | {8} |

| S2 | Llama-7B | 4096 | {64, 32, 16, 8} |

| S4 | Llama-13B | 5120 | {64, 32, 16} |

| S5 | Llama-30B | 7168 | {32} |

| S6 | Llama-70B | 8192 | {64} |

Baselines

We compare S-LoRA with HuggingFace PEFT and vLLM.

- PEFT stands for HuggingFace PEFT: We build a server using it that batches single adapter requests and switches adapter weights between batches.

- vLLM-packed: Since vLLM does not support LoRA, we merge the LoRA weights into the base model and serve the multiple versions of the merged weights separately. To serve m LoRA adapters, we run

mvLLM workers on a single GPU, where multiple workers are separate processes managed by NVIDIA MPS. - S-LoRA is S-LoRA with all the optimizations and it is using the first-come-first-serve scheduling strategy.

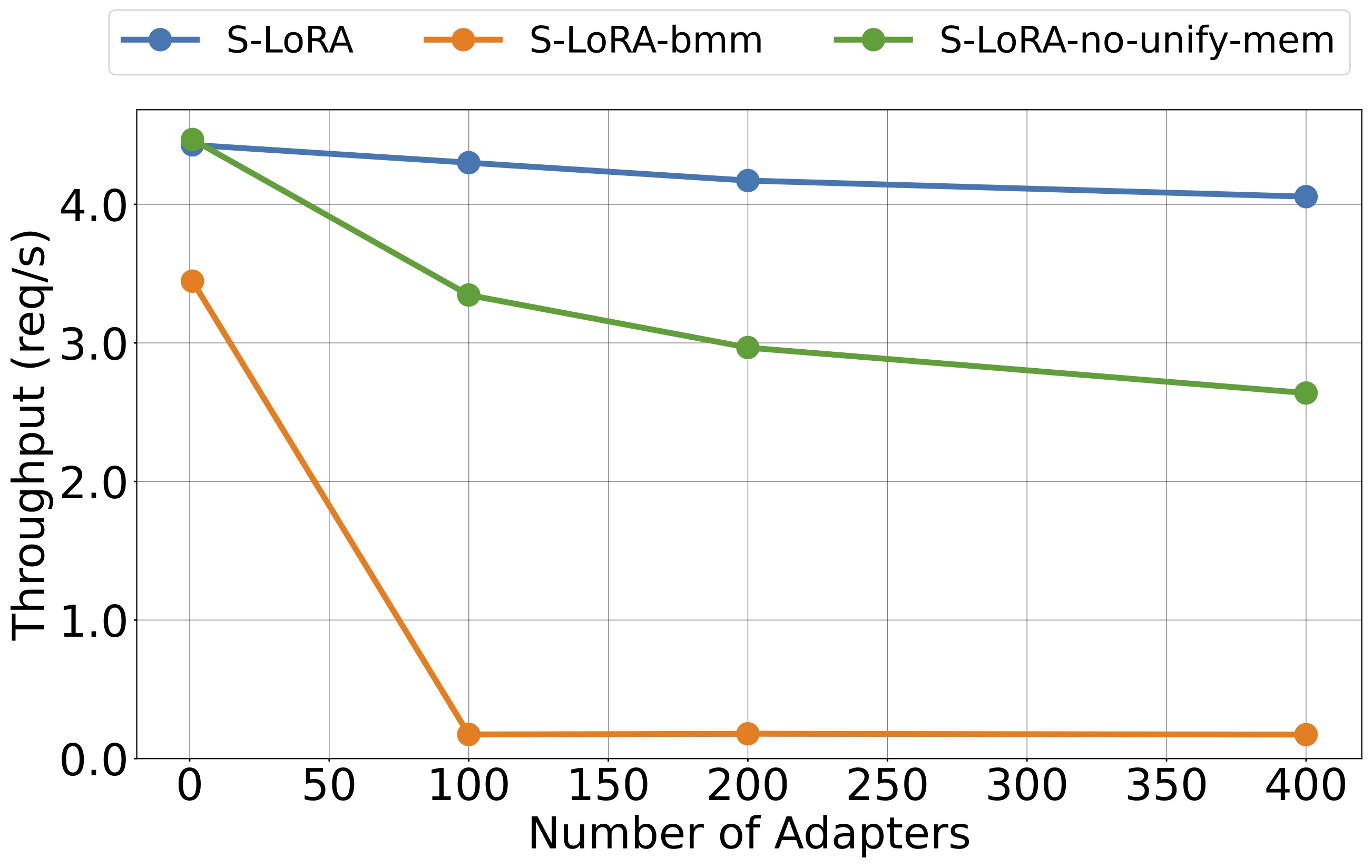

- S-LoRA-no-unify-mem is S-LoRA without the unified memory management.

- S-LoRA-bmm is S-LoRA without unified memory management and customized kernels. It copies the adapter weights to contiguous memory space and performs batched matrix multiplication with padding.

Throughput

The table below shows the throughput (req/s) comparison between S-LoRA, vLLM-packed, and PEFT. The hardware is a single A100 (80GB). We run PEFT for a shorter duration when $n=100$. We do not evaluate PEFT for $n\geq 1000$, as its throughput is already very low for a small $n$. "OOM" denotes out-of-memory.

| Model Setup | n | S-LoRA | vLLM-packed | PEFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 5 | 8.05 | 2.04 | 0.88 |

| 100 | 7.99 | OOM | 0.25 | |

| 1000 | 7.64 | OOM | - | |

| 2000 | 7.61 | OOM | - | |

| S2 | 5 | 7.48 | 2.04 | 0.74 |

| 100 | 7.29 | OOM | 0.24 | |

| 1000 | 6.69 | OOM | - | |

| 2000 | 6.71 | OOM | - | |

| S4 | 2 | 4.49 | 3.83 | 0.54 |

| 100 | 4.28 | OOM | 0.13 | |

| 1000 | 3.96 | OOM | - |

Remarkably, S-LoRA can serve 2,000 adapters simultaneously, maintaining minimal overhead for the added LoRA computation. In contrast, vLLM-packed needs to maintain multiple weight copies and can only serve fewer than 5 adapters due to the GPU memory constraint. The throughput of vLLM-packed is also much lower due to the missed batching opportunity. Overall, S-LoRA achieves a throughput up to 4x higher than vLLM-packed when serving a small number of adapters, and up to 30x higher than PEFT, while supporting a significantly larger number of adapters.

Compared with our own variants, S-LoRA achieves noticeably higher throughput and lower latency compared to S-LoRA-bmm and S-LoRA-no-unify-mem. This implies that our designs are effective. When the number of adapters increases, the throughput of S-LoRA initially experiences a slight decline due to the overhead introduced by LoRA. However, once the number of adapters reaches a certain threshold, the throughput of S-LoRA no longer decreases.

Figure 7: The throughput of S-LoRA and its variants under different number of adapters (S4@A100-80G). S-LoRA achieves significantly better performance and can scale to a large number of adapters.

S-LoRA TP Scalability

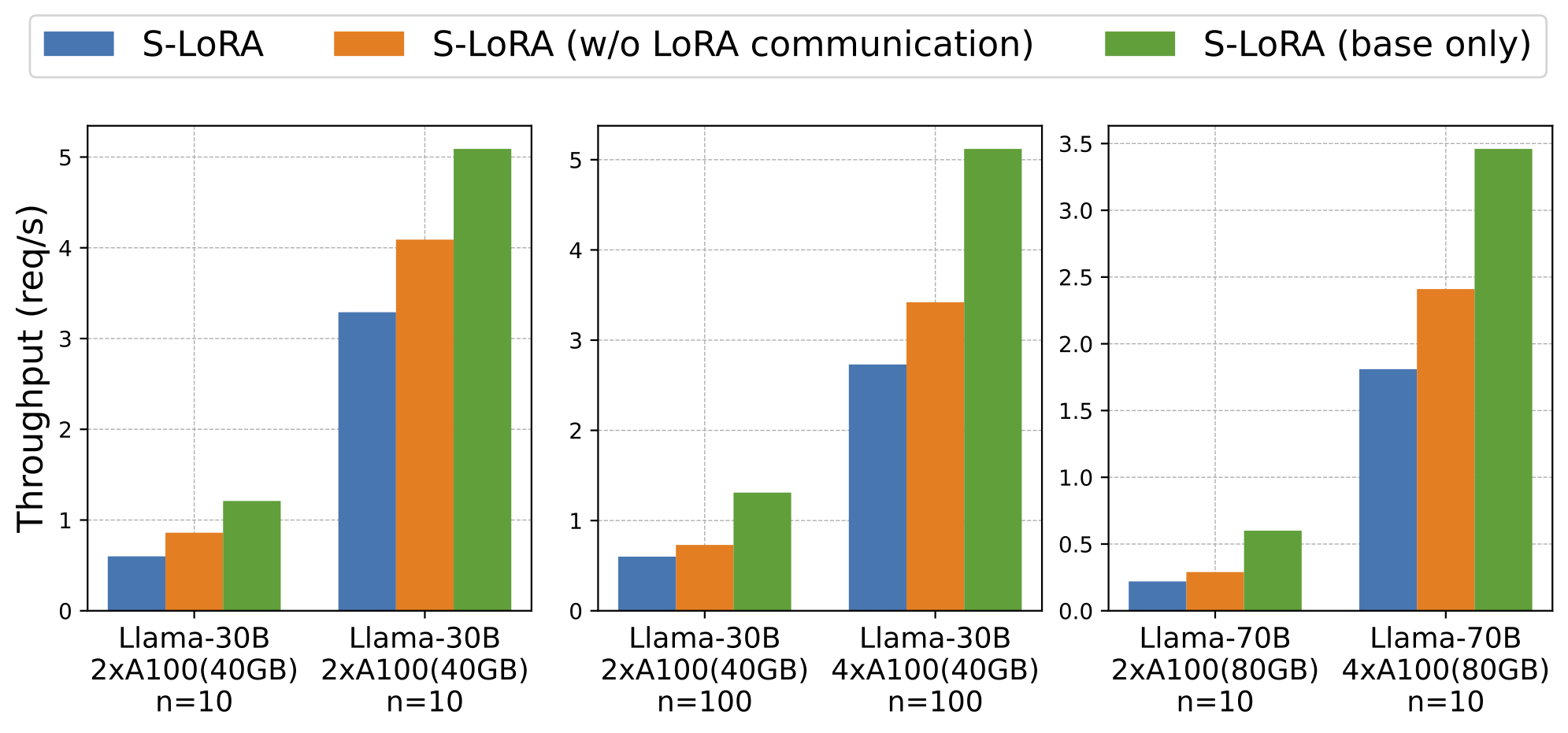

We test the scalability of our tensor parallelism strategy by running 1. Llama-30B on two A100 (40GB) and four A100 (40GB) GPUs with 10 to 100 adapters; and 2. Llama-70B on two A100 (80GB) and four A100 (80GB) GPUs with 10 adapters.

As depicted in the figure below, the disparity between S-LoRA with and without LoRA communication is small. This suggests that the added LoRA communication in our strategy has a very small overhead. The figure further reveals that the communication overhead due to LoRA is less than the computational overhead it introduces. Furthermore, when transitioning from 2 GPUs to 4 GPUs, the serving throughput increases by more than 2 times. This significant increase can be attributed to the fact that the system is predominantly memory-bound in this context. Adding more GPUs alleviates memory constraints, leading to superlinear scaling. In conclusion, the results verify both the minimal overhead and the scalability of our tensor parallelism strategy.

Figure 8: Throughput with S-LoRA TP.

Please check our paper for more results on S-LoRA variants and other ablation studies.

Citation

@misc{sheng2023slora,

title={S-LoRA: Serving Thousands of Concurrent LoRA Adapters},

author={Ying Sheng and Shiyi Cao and Dacheng Li and Coleman Hooper and Nicholas Lee and Shuo Yang and Christopher Chou and Banghua Zhu and Lianmin Zheng and Kurt Keutzer and Joseph E. Gonzalez and Ion Stoica},

year={2023},

eprint={2311.03285},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.LG}

}