Unified FP8: Moving Beyond Mixed Precision for Stable and Accelerated MoE RL

by: InfiXAI Team, Ant Group AQ Team, SGLang RL Team, Miles Team, Nov 25, 2025

TL;DR: We have implemented fully FP8-based sampling and training in RL. Experiments show that for MoE models, the larger the model, the more severe the train–inference discrepancy becomes when using BF16 training with FP8 rollout. In contrast, using unified FP8 for both training and rollout effectively eliminates train–inference inconsistency caused by quantization error, improving both the speed and stability of RL training.

SGLang RL Team and the Miles community have conducted some interesting explorations around RL training stability and acceleration:

Aligning the SGLang and FSDP backends for strictly zero KL divergence

Speculative Decoding with online SFT for the draft model

Building on this, we now share a new progress that balances both stability and performance—implementing an end-to-end FP8 pipeline for RL training and sampling. FP8 RL training for Qwen3-4B and Qwen3-30B-A3B has been fully supported in miles and is ready to use out of the box.

This work is jointly completed by the InfiXAI Team, Ant Group AQ Team, SGLang RL Team, and Miles Team. Special thanks to DataCrunch for compute sponsorship and to NVIDIA for technical support on Transformer Engine (TE).

Hardware Foundations of FP8 Training

Tensor Cores and Low-Precision Support

Low-precision computing is a gem of hardware–software co-design. We first introduce its hardware foundation—Tensor Cores, a type of GPU hardware acceleration unit designed specifically for large-scale matrix multiplication and accumulation, the core computation in deep learning. Compared with traditional CUDA cores, Tensor Cores can process low-precision data formats (such as FP16, BF16, FP8) with much higher throughput. Their evolution began with basic FMA (fused multiply–add) instructions and early vectorization through DP4A, but the real milestone came with the Volta architecture, which first introduced Tensor Cores as dedicated units for large-scale matrix operations. Since then, Ampere, Hopper, and the latest Blackwell architectures have continued to push this idea further:

- Scaling up: Letting Tensor Cores process larger matrices per operation, thereby improving compute-to-memory ratios.

- Lowering precision: Continuously adding support for FP/BF16, FP8, and even lower-precision data formats.

| Arch | FP64 | F16 | INT8 | INT4 | FP8 | MXFP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volta | ❌ | ✅ FP16 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Turing | ❌ | ✅ FP16 | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Ampere | ✅ | ✅ FP16/BF16 | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Hopper | ✅ | ✅ FP16/BF16 | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ (accumulation precision only supports FP22) | ❌ |

| Blackwell | ✅ | ✅ FP16/BF16 | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ MXFP(8/6/4) NVFP4 |

| Blackwell Ultra | ✅ (reduced FLOPs) | ✅ FP16/BF16 | ✅ (reduced FLOPs) | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ MXFP(8/6/4) NVFP4 |

Figure source: zartbot, SemiAnalysis

Under this hardware trend, using lower precision for storage and computation becomes increasingly attractive. Concretely, lower-precision floating-point formats offer several potential advantages:

- Significantly reduced memory footprint: Compared with mainstream BF16, FP8 can theoretically halve the memory consumed by model weights and activations, directly alleviating ever-growing VRAM pressure.

- Theoretically 2× compute throughput: On mainstream GPUs (e.g., H100 SXM), FP8 Tensor Cores offer up to 1979 TFLOPS of theoretical performance, twice that of BF16 units (989 TFLOPS). This substantial performance gain is a key driver behind FP8 training.

- Mitigated memory bandwidth bottlenecks: With more compact data representation, less data must be transferred from GPU HBM to compute cores. This means less time spent on data movement and effectively reduces memory-bandwidth pressure.

FP8 Formats

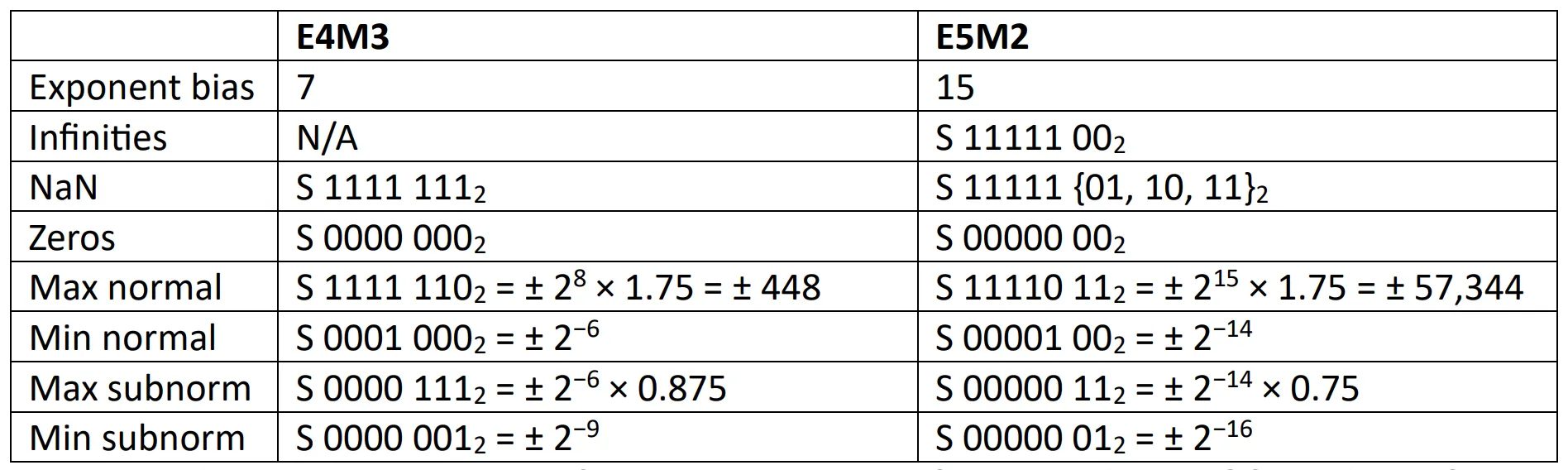

FP8 is a floating-point format that uses 8 bits to represent values. Compared with FP32 (32 bits) and FP16/BF16 (16 bits), FP8 can reduce storage and transmission costs for the same amount of data to 1/4 or 1/2, greatly easing VRAM and bandwidth bottlenecks and improving training and inference performance. Currently, there are two major FP8 formats:

- E4M3: 4-bit exponent + 3-bit mantissa. Smaller dynamic range but higher precision.

- E5M2: 5-bit exponent + 2-bit mantissa. Larger dynamic range but lower precision.

Figure source: OCP whitepaper

This design allows FP8 to maintain sufficient numerical range and precision while maximizing hardware throughput.

FP8 Scale Selection

| Dimension | FP32 Scale (full-precision scaling factor) | E8M0 Scale (exponent-only scaling) |

|---|---|---|

| Format definition | FP32 (IEEE 754 single-precision float) | E8M0 (8-bit exponent, 0-bit mantissa) |

| Numeric properties | Can represent real numbers with arbitrary precision. | Only supports powers of 2, such as 1, 2, 0.5; cannot represent values like 1.5. |

| Core idea | Manage scaling factors in high precision to ensure numerical stability during training. | Bring scaling factors into the low-precision regime and leverage bit operations for efficiency. |

| Main advantages | 1. High precision, stable training: Accurately captures dynamic ranges, reduces quantization error, and prevents divergence. 2. Broad support: Default choice in mainstream libraries such as NVIDIA Transformer Engine; mature ecosystem. |

1. Extremely hardware-friendly: Scaling can be implemented as simple bit shifts, which are very fast and energy-efficient. 2. Unified pipeline: The entire pipeline (including scale) runs in 8 bits, simplifying hardware design. |

| Main disadvantages | 1. Storage overhead: Each quantized tensor needs to store one extra FP32 scale value, consuming some VRAM. 2. Compute overhead: Scale calculations and conversions must be done in FP32. |

1. Precision-loss risk: Forcing rounding to powers of 2 introduces quantization noise, which can accumulate during backprop and cause divergence. 2. Limited dynamic-range resolution: Harder to finely adapt to complex tensor distributions. |

| Summary | Currently the most common and safest scheme in industry. | Sacrifices some precision in exchange for extreme hardware efficiency. |

After a comprehensive evaluation, we ultimately chose FP32 as the scale precision during training. The reasons are:

- Precision alignment and training stability: FP32 scales provide fine-grained numerical scaling that captures tensor dynamic ranges and keeps FP8 training loss curves as close as possible to the BF16 baseline.

- Consistency with inference ecosystems: Mainstream inference models also use FP32 as the quantization scale format.

- Real-world hardware benefits:

- Hopper (H100/H800): Although it supports FP8 Tensor Cores, it has no dedicated compute units for E8M0 scaling.

- Blackwell (B100/B200): Introduces support for MXFP8 (micro-scaling), which provides hardware acceleration for block-level scaling like E8M0 (see arXiv:2506.08027).

Therefore, under current H-series clusters, forcing the use of E8M0 not only fails to deliver clear speedups, but may also introduce additional software-emulation overhead and precision risks.

FP8 Quantization

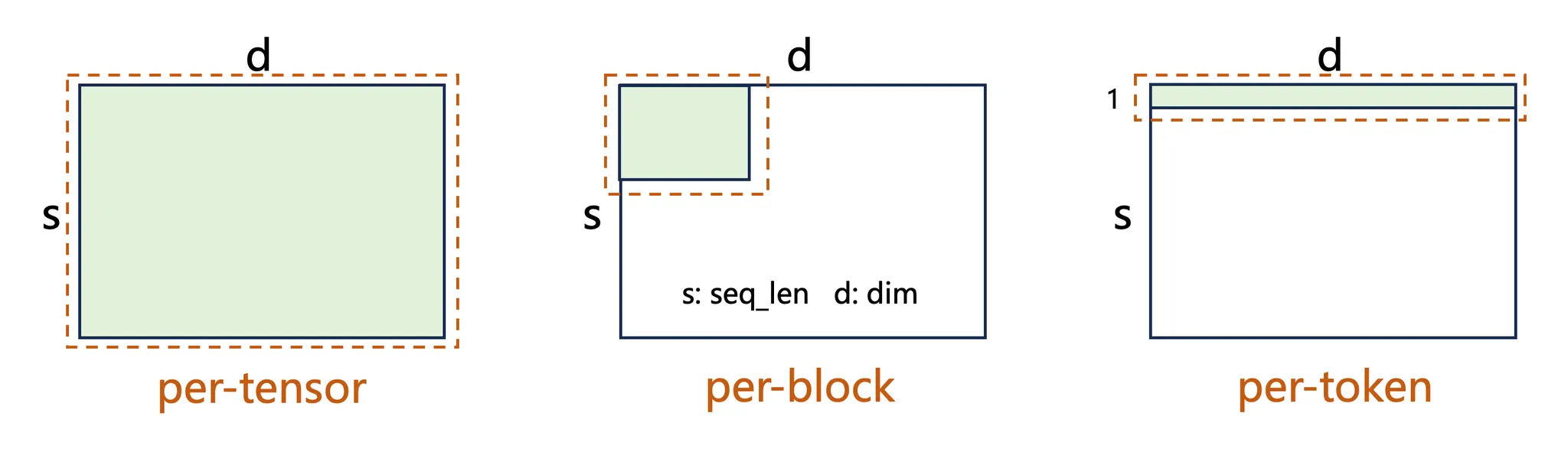

Common quantization strategies include per-tensor, per-block, and per-token. Regardless of granularity, quantization usually follows two simple steps:

Figure source: InfiR2: A Comprehensive FP8 Training Recipe for Reasoning-Enhanced Language Models

Step 1: Compute the scaling factor $S$

Take the maximum absolute value $\max|X|$ in a given tensor (or block) and divide it by the maximum representable FP8 value $V_{\max}$:

$$ S = \frac{\max|X|}{V_{\max}} $$

Step 2: Compute the quantized value $Q$

Using the scaling factor $S$, divide each element $x$ in the original tensor $X$ by $S$ and round to the nearest integer to obtain quantized values:

$$ Q(x) = \mathrm{round}\left(\frac{x}{S}\right) $$

Because FP8 has lower precision than FP16/BF16, we must trade off between training stability and efficiency in practice, so forward and backward passes often use different quantization strategies and granularities:

- Activations: Typically use per-token quantization. Activations often contain significant outliers; finer quantization granularity can localize the effect of outliers and better preserve overall precision.

- Weights: Typically use per-block quantization. After convergence, weight distributions are usually smooth (close to Gaussian) with few outliers, but are highly sensitive to quantization error. Blockwise quantization (e.g., block_size × block_size) maintains precision while working well with hardware optimizations, balancing compute efficiency and memory savings.

- Gradients: Typically use per-token quantization. Gradients have large dynamic-range variation but relatively low absolute precision requirements. Historically, most schemes used per-tensor E5M2 to ensure dynamic range, but DeepSeek-V3 shows that fine-grained E4M3 can also balance precision and range.

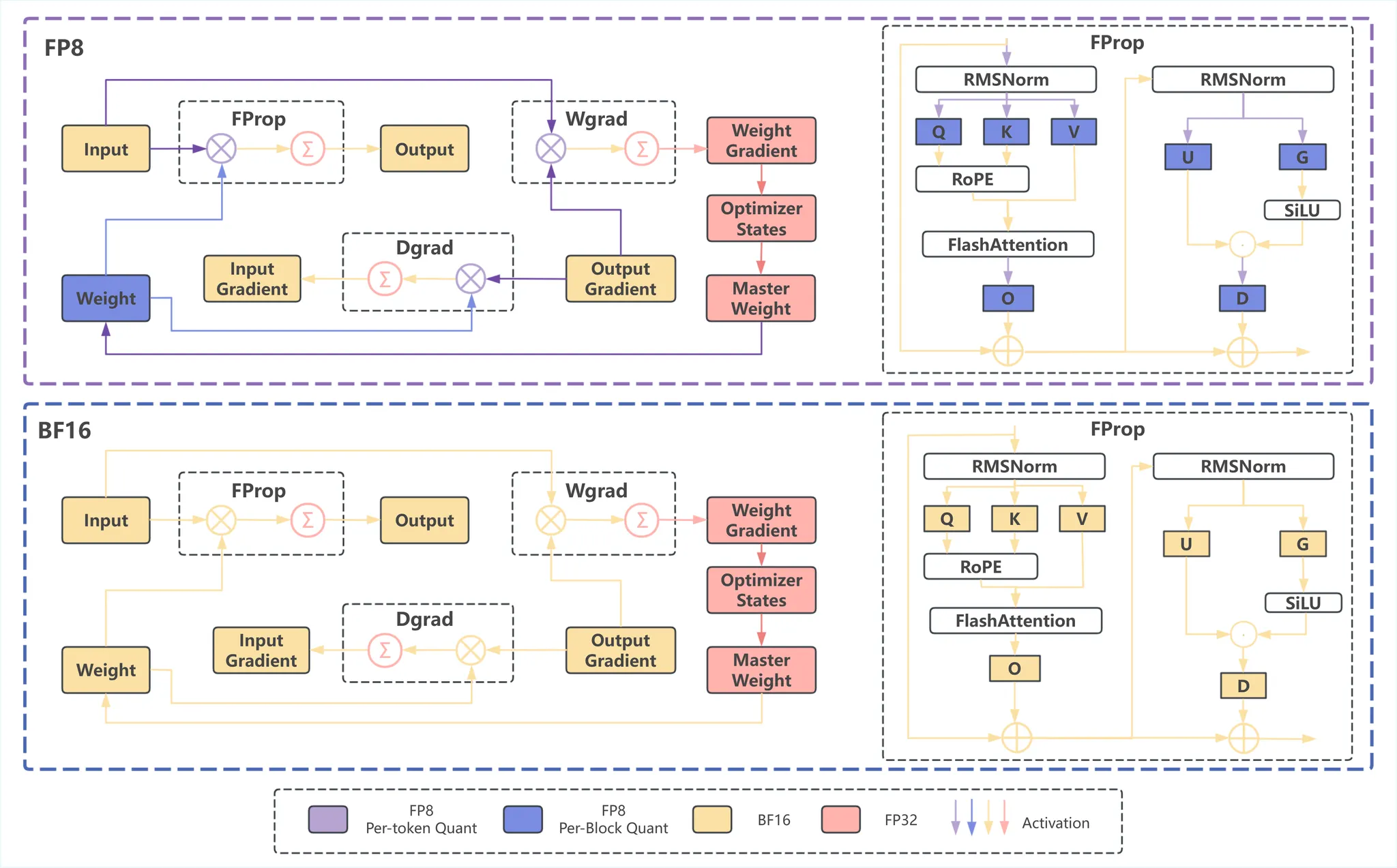

Figure source: InfiR2: A Comprehensive FP8 Training Recipe for Reasoning-Enhanced Language Models

The figure shows the mixed-granularity FP8 strategy used in Megatron compared to a standard BF16 pipeline. In the FP8 pipeline, different quantization methods are applied: weights use per-block quantization (blue), while activations use per-token quantization (purple). The figure presents the full training process, including forward propagation (FProp), weight-gradient computation (Wgrad), and input-gradient computation (Dgrad), and details the FProp workflow.

Challenges of FP8 Training

Although FP8 shows great potential, in real engineering practice—especially when combining Megatron-Core and TransformerEngine (TE)—we encounter three main challenges: memory/efficiency not meeting expectations, difficulty aligning precision, and stability issues in the framework itself. We refer to our unified FP8 training-and-inference setup as FP8-TI (FP8 Training & Inference).

Memory and Compute Efficiency: Theory vs. Reality

In practice, the memory savings and speedups brought by FP8 are often less significant than theory suggests, mainly due to:

- Limited memory optimization:

- Redundant weight copies: To speed up backprop, TransformerEngine keeps an extra transposed copy of quantized weights. This prevents weight memory usage from being reduced by the expected factor of 2.

- High-precision activation copies: In the forward pass of attention and activation layers, frameworks typically retain a high-precision copy of activations for accurate gradient computation later. FP8 does not reduce this portion of memory usage.

- Compute-efficiency bottlenecks:

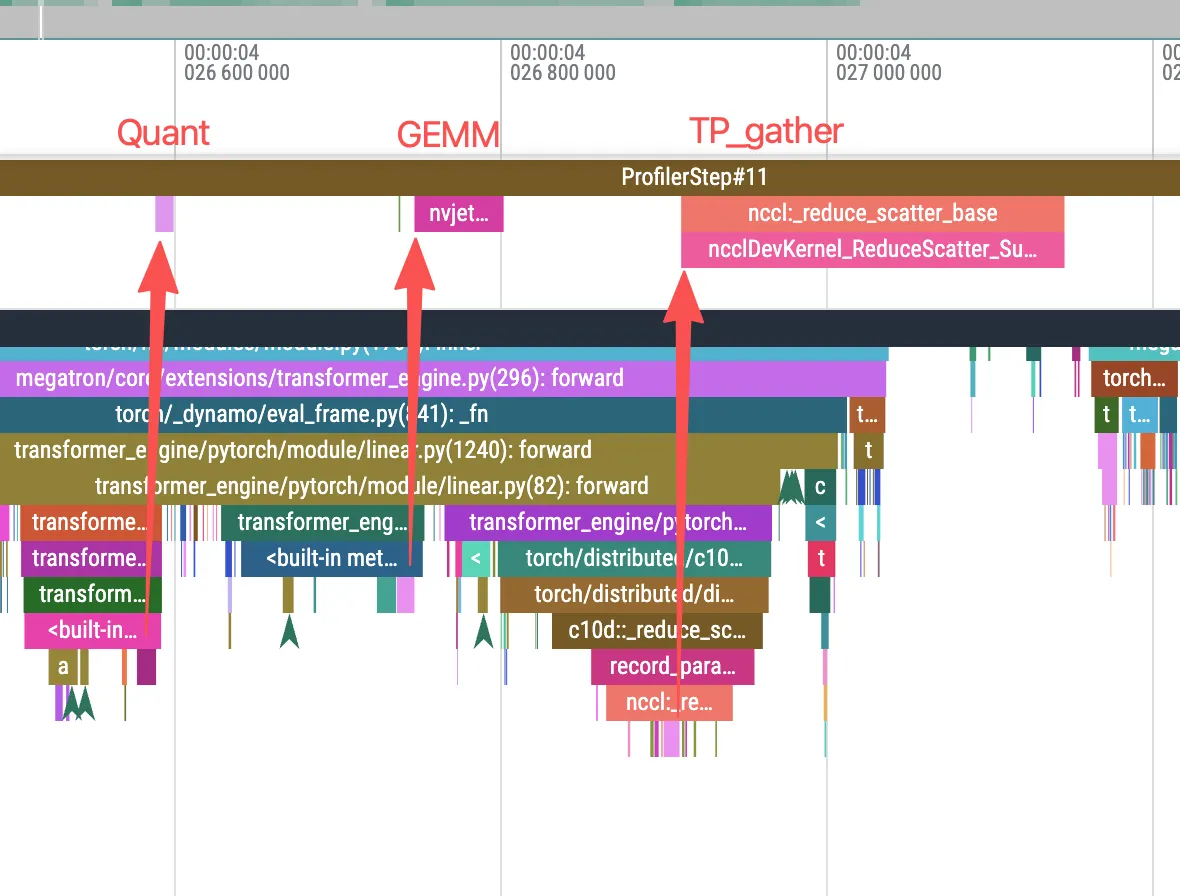

- Performance degradation with small batch sizes: When batch_size is small, FP8 training may fail to fully utilize GPU compute units and can even underperform BF16. The root cause is that FP8 introduces extra quantization and dequantization operations, which add CPU overhead. In Agentic RL scenarios, which typically use small batch sizes (e.g., batch_size=4), this issue is particularly pronounced—frequent CPU overhead can make FP8 training slower than BF16. (As shown below, GPU kernels are not densely scheduled; often the GPU has already finished the previous work but the next kernel launch is delayed because the system is CPU-bound.)

Figure: CPU-bound behavior in FP8 training

Precision Alignment: Cumulative Error Matters

The low-precision nature of FP8 inherently introduces numerical discrepancies relative to BF16, which can be amplified in deep models and cause training-instability problems:

- Intrinsic quantization error: Even if accumulation is performed in FP32, quantizing FP8 inputs for a single GEMM operation introduces error. Experiments show that compared with BF16 GEMM, the typical error is about 0.0007.

- Layer-wise cumulative effect: In deep Transformer models, these small errors accumulate layer by layer during forward and backward passes:

- In pre-training and fine-tuning (SFT): Gradients are mainly dominated by the log probabilities of ground-truth labels. With fine-grained blockwise quantization, errors can usually be kept within an acceptable range and models are unlikely to collapse.

- In reinforcement learning (RL): Gradients are often determined by the difference between two log probabilities from two forward passes. In this case, accumulated FP8 error can be amplified, causing gradients to deviate from their ideal direction and impacting convergence efficiency—or even pushing the optimization “in the wrong direction” (as discussed later).

Framework Adaptation: TransformerEngine Version Compatibility

Besides algorithmic challenges, there is room for improvement in how Megatron-Core integrates with Transformer Engine (TE), especially given TE’s rapid iteration:

- Version dependencies and migration overhead: TE’s fast iteration brings new features but also strict version dependencies. In practice, we found that even the same training script can yield different numerical behaviors across TE versions, and sometimes code adjustments are required to avoid issues such as NaNs.

- Maturity for specific architectures: Full FP8 support for all mainstream model architectures is an ongoing process. For some nonstandard or newer components (such as MLA), we observed that FP8 training support is still maturing. Even in later versions (e.g., 2.4.0 → 2.8.0), certain errors and limitations remain to be resolved.

- Conflicts with memory-optimization strategies: In RL training, enabling Optimizer CPU Offload can significantly reduce memory usage, but current TE does not support using it together with

--fp8-param-gather. Because of this limitation, end-to-end FP8 training can end up consuming more memory than BF16 training with FP8 rollout, which needs further optimization from the community and maintainers.

FP8 + RL: Attributing Abnormal KL Loss

The InfiXAI Team has already successfully run full FP8 training on pre-training and fine-tuning tasks (see Pre-training and Fine-tuning). Building on this, we apply FP8 training to RL. Thanks to Miles' good support for Megatron FP8 training, we were able to run a series of FP8 RL experiments smoothly.

Abnormal Initial KL Loss

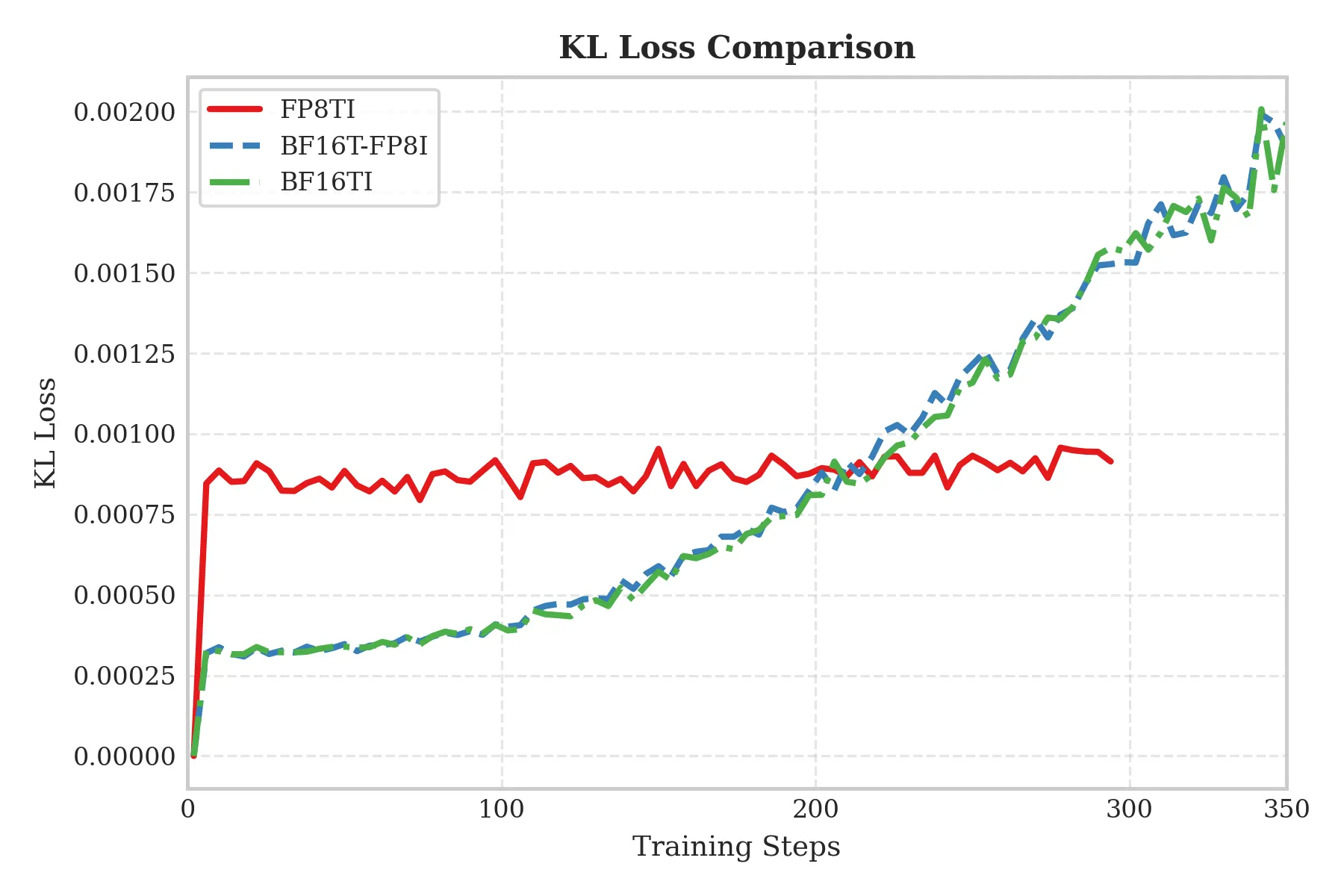

When we directly switched from BF16 to FP8 and started training, we observed a striking phenomenon: compared with BF16 training, FP8 training has a significantly higher KL loss at the first step. As shown below, the initial KL loss for FP8-TI is significantly higher than that of BF16 training with FP8 inference (T denotes Training, I denotes Inference):

Locating the Source of Error

To understand why initial KL loss is higher, we analyze two potential error sources in the quantization process:

- Error from quantized compute kernels: Numerical error from specific FP8 GEMM implementations.

- Intrinsic quantization error: Precision loss from quantization and dequantization themselves.

Error analysis of quantized compute kernels

Initially, we suspected that the closed-source cuBLAS GEMM implementation used in TransformerEngine might be less accurate than the widely used open-source DeepGEMM, so we designed experiments to compare the precision of these two FP8 GEMM implementations against BF16. We evaluated their errors under various shapes (based on TE’s test cases), with results shown below:

| Kernel (M, K, N) | cuBLAS(TE) | DeepGEMM |

|---|---|---|

| 128,128,128 | 0.00068 | 0.00036 |

| 256,128,256 | 0.00068 | 0.00037 |

| 320,128,336 | 0.000684 | 0.00037 |

| 320,64,336 | 0.00067 | 0.00024 |

| 320,256,336 | 0.00068 | 0.00048 |

| 1024,4096,1024 | 0.000681 | 0.00065 |

| 2048,2048,512 | 0.00068 | 0.00063 |

| 1024,1024,1024 | 0.000683 | 0.0006 |

The results show that the errors of the two GEMM implementations are of the same order of magnitude with no significant difference, so replacing TE’s FP8 GEMM does not reduce the initial KL loss.

Analysis of intrinsic quantization error

For the second potential source, we designed a set of comparative experiments to isolate and validate the intrinsic error of quantization:

- Baseline: Qwen3-4B on a single H800.

- Experimental modes:

- Baseline: Weights and inputs in BF16, using BF16 GEMM.

- FP8 Real Quant: Weights and inputs in FP8, using FP8 GEMM (e.g., DeepGEMM/cuBLAS GEMM; we mainly tested cuBLAS to avoid large changes to TE).

- FP8 Fake Quant: Weights and inputs kept in BF16, but we simulate the quantization process (quantize to FP8 then dequantize back to BF16), and finally use BF16 GEMM.

Based on these modes, we run two comparisons:

- FP8 Real Quant vs. FP8 Fake Quant: To verify the precision of the FP8 GEMM kernels (cuBLAS), isolating any additional error from the implementation.

- Baseline vs. FP8 Fake Quant: To ignore GEMM kernel effects and focus on the intrinsic error introduced by quantization/dequantization themselves.

Metric: We collect the output differences (Diff) of all GEMM operations at the beginning of RL training (Step 0 and Step 1).

Results:

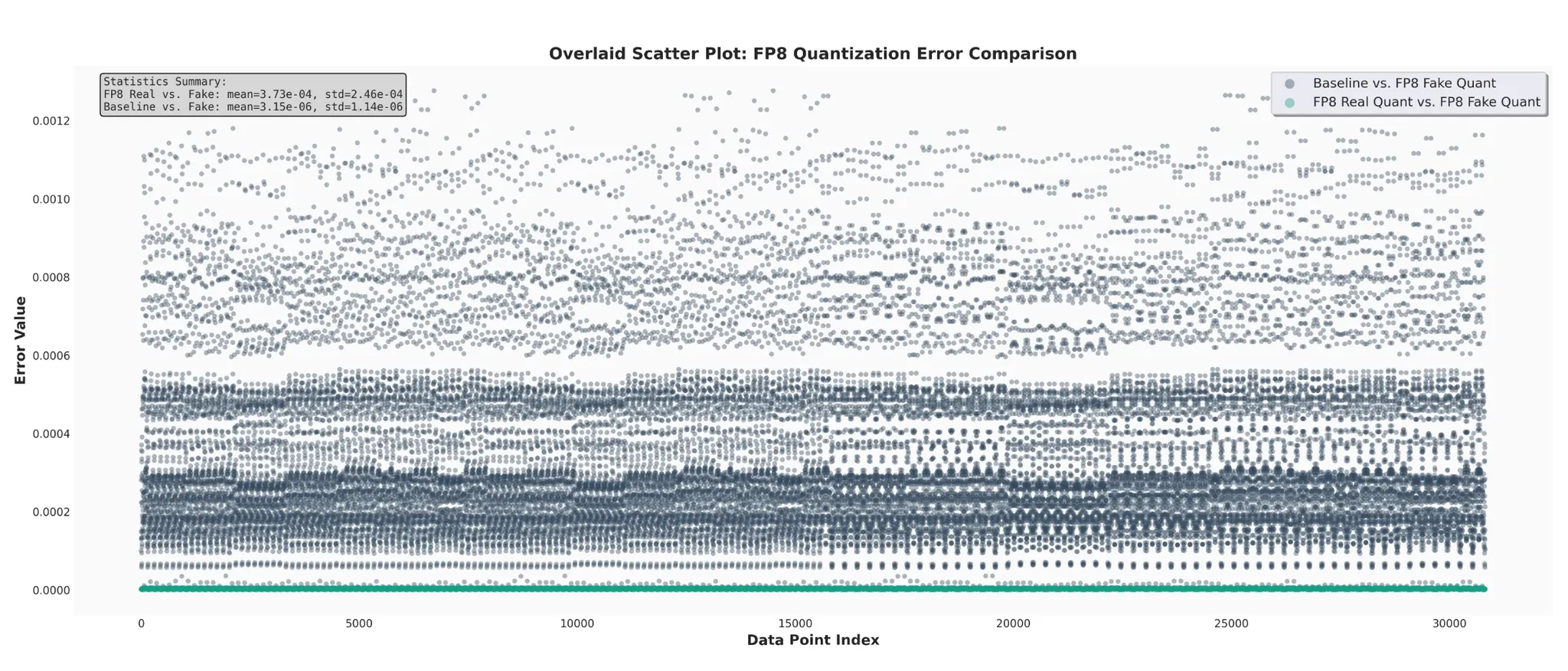

The figure below visualizes the error distribution of all GEMM outputs over one full forward + backward pass, in execution order:

The figure shows how GEMM output errors evolve over one full iteration.

- Grey/high points (Baseline vs. FP8 Fake Quant): Represent error from quantization itself. We can see significant differences between the BF16 baseline and fake quantization.

- Green/low points (FP8 Real Quant vs. FP8 Fake Quant): Represent error from the kernel implementation. These differences are extremely small, nearly zero.

From this we conclude:

- Error mainly comes from the quantization principle, not the kernel implementation: Both Fake Quant and Real Quant differ significantly from the baseline (by two orders of magnitude), strongly indicating that the dominant error source is the lossy quantization/dequantization itself, rather than computation.

- FP8 GEMM kernels are highly reliable: The tiny difference between Real Quant and Fake Quant outputs shows that the cuBLAS FP8 GEMM we use in TE is extremely accurate and closely matches the ideal mathematical simulation, making it safe for production.

How Quantization Error Leads to Training Anomalies

Based on the above experiments, we hypothesize:

- The main error in training is already introduced at the quantization step and is substantial.

- The higher initial KL loss in FP8 training likely comes from this quantization error.

- In hybrid BF16 training + FP8 inference (rollout), the same quantization error also causes train–inference inconsistency.

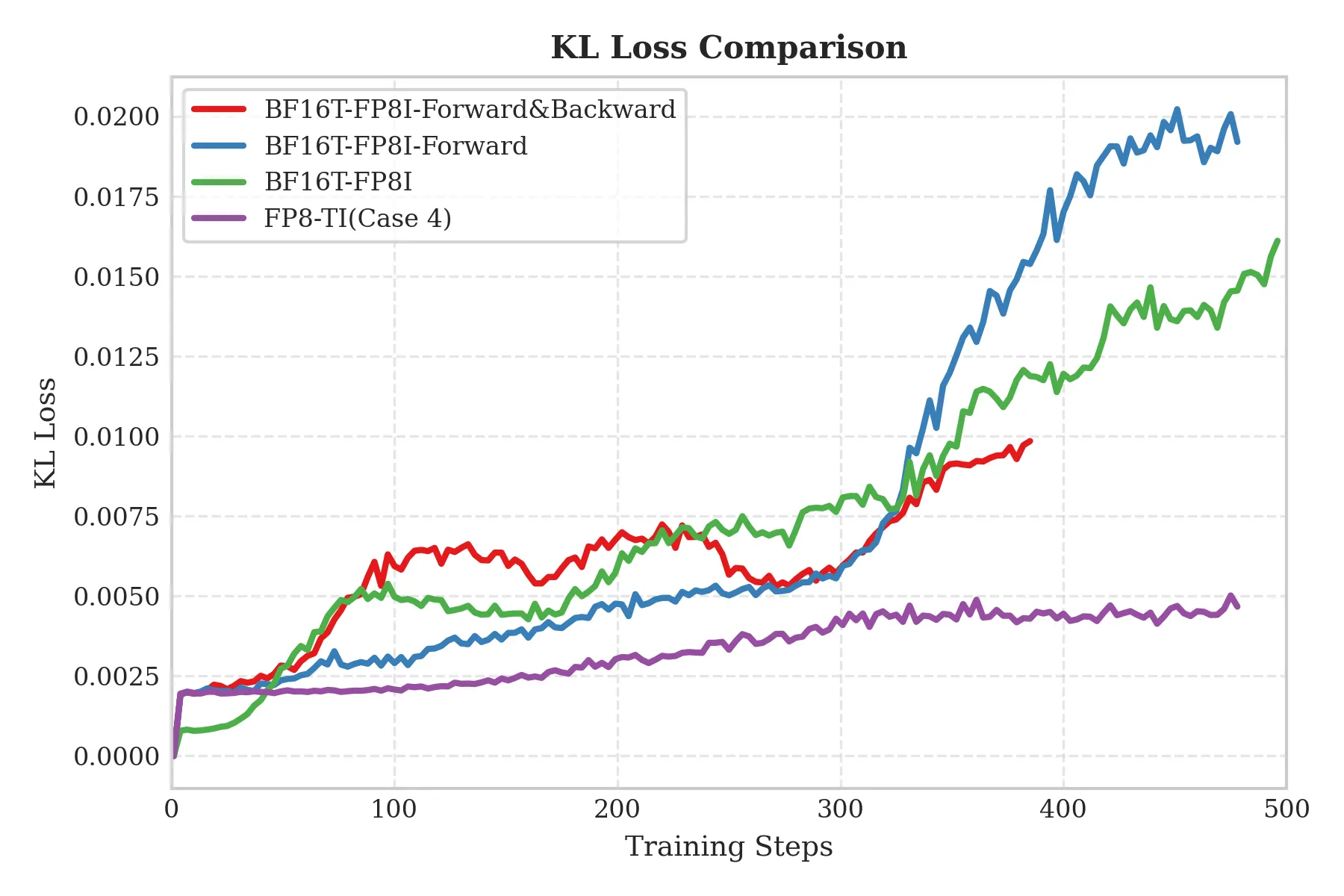

To validate these hypotheses, we modified Transformer Engine (TE) and designed the following experiments:

- Baseline: Qwen3-4B on an H800 cluster.

- Cases:

- Case 1: BF16 training, FP8 rollout (inference).

- Case 2: BF16 training, FP8 rollout; in the forward pass during training, quantize BF16 weights and activations to FP8 then dequantize back to BF16 before running BF16 GEMM.

- Case 3: BF16 training, FP8 rollout; in both forward and backward passes during training, quantize both input matrices A and B to FP8 then dequantize back to BF16 before BF16 GEMM.

- Case 4 (FP8-TI): FP8 training, FP8 rollout.

Validating hypothesis 2 — KL-loss analysis

The figure below shows KL-loss curves for the four cases. We see that Case 2, Case 3, and Case 4 (FP8-TI) have nearly identical KL loss at step 1, all significantly higher than Case 1:

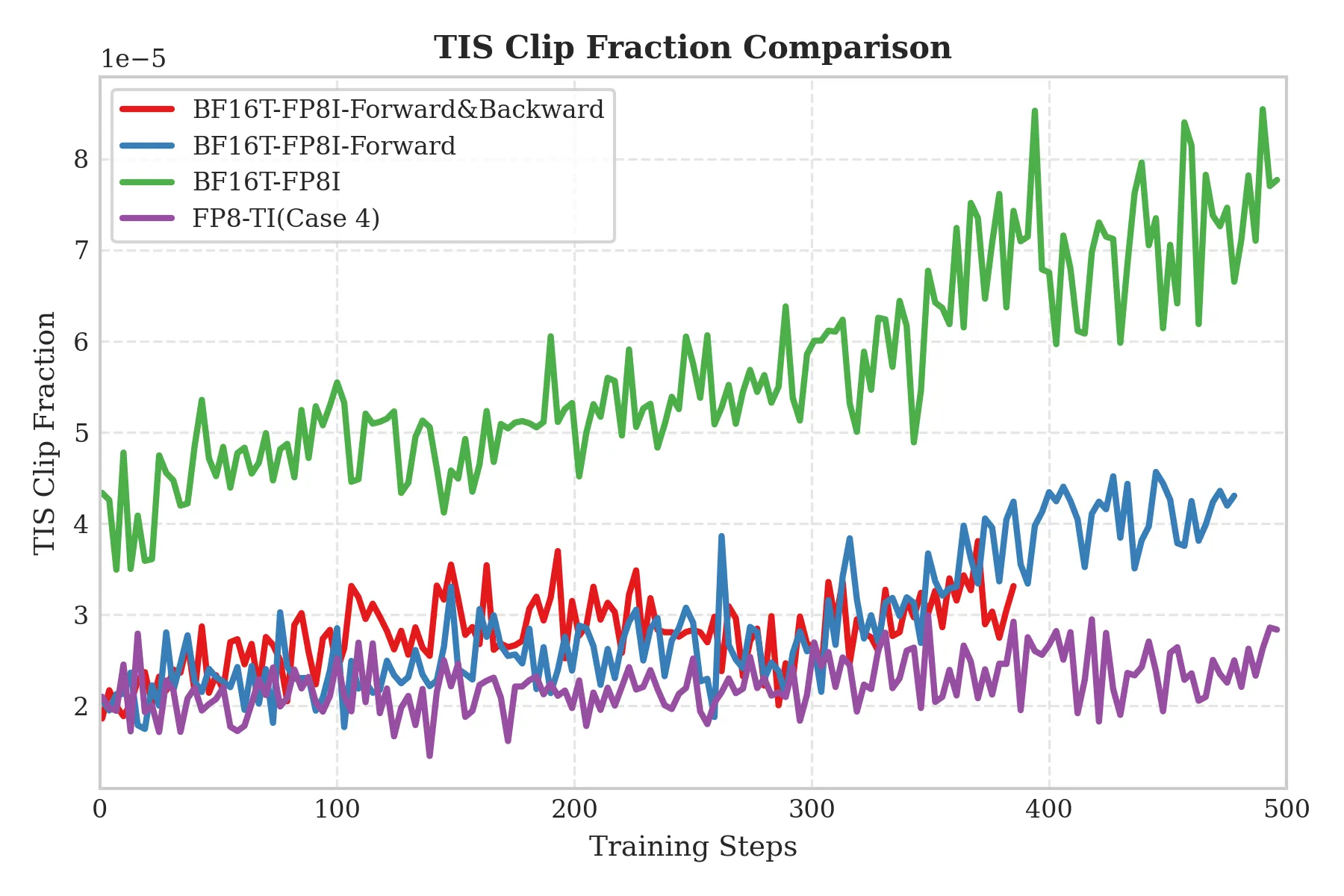

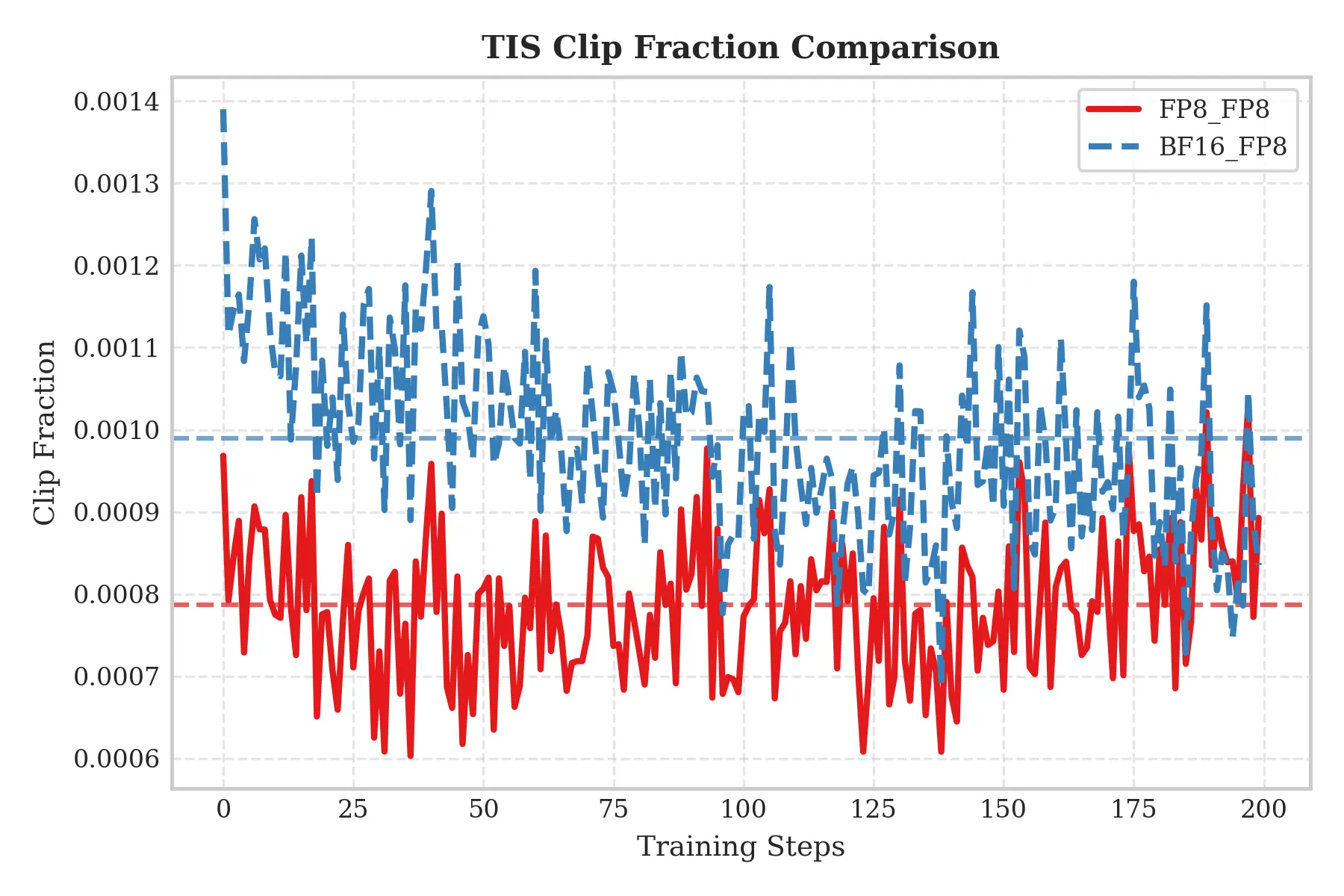

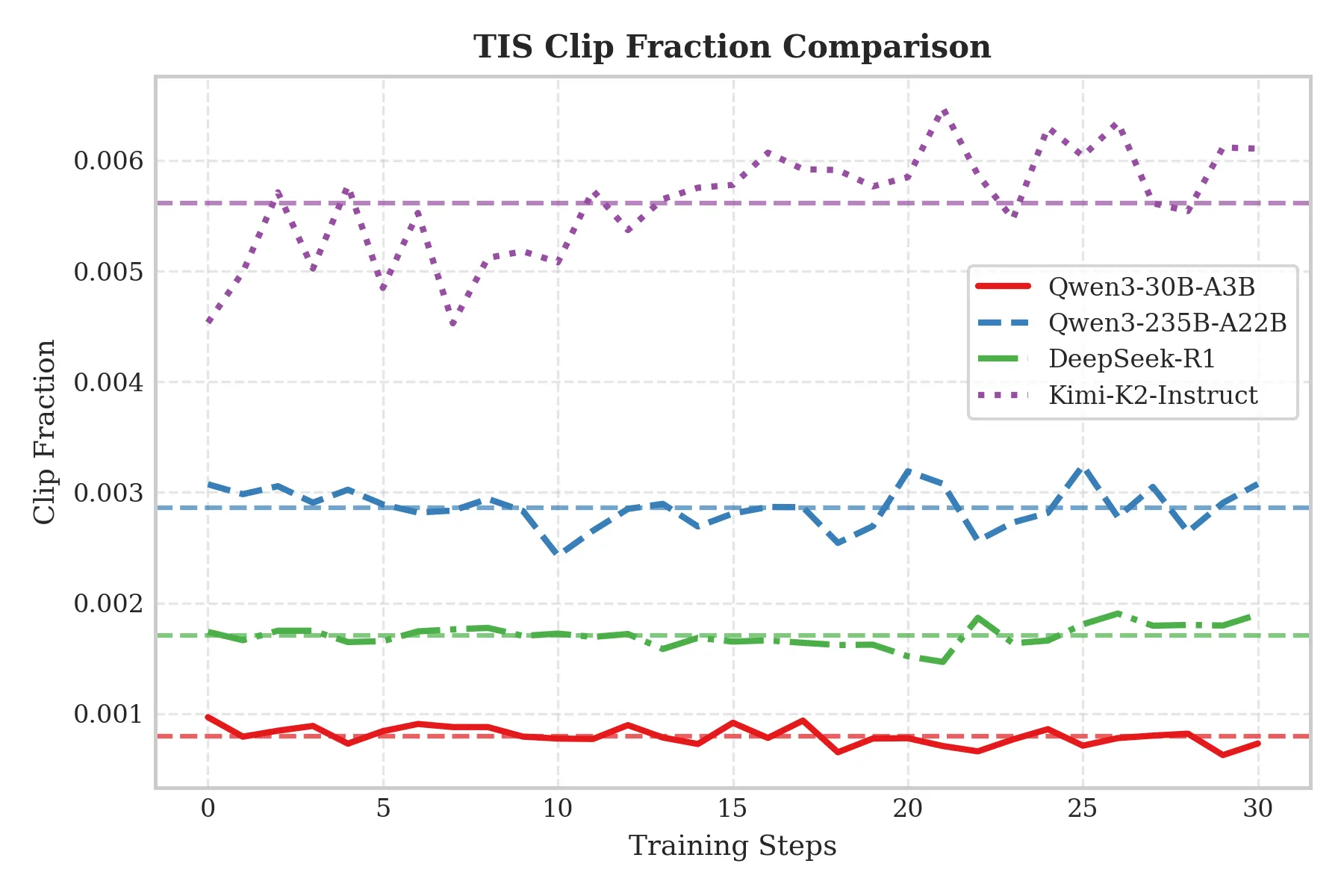

Validating hypothesis 3 — TIS-clipfrac analysis

We introduce clipfrac from Truncated Importance Sampling (TIS) to validate hypothesis 3. This metric reflects the degree of off-policy training, i.e., the consistency between the model used for training and for generating experience. Higher clipfrac generally indicates more severe train–inference inconsistency.

From the figure we see that Case 2, Case 3, and Case 4 (FP8-TI) have clipfrac values of roughly the same order, all significantly lower than Case 1. This confirms:

- The root cause of the elevated initial KL loss is quantization error.

- FP8-TI (Case 4) can significantly alleviate train–inference inconsistency compared with the hybrid BF16 training + FP8 rollout (Case 1).

- For training bias, quantization error in the forward pass matters more than in the backward pass (as shown by the similarity between Case 2 and Case 3). Similarly, for train–inference consistency, forward quantization error is the primary factor.

Applying FP8 to MoE RL: Experiments and Validation

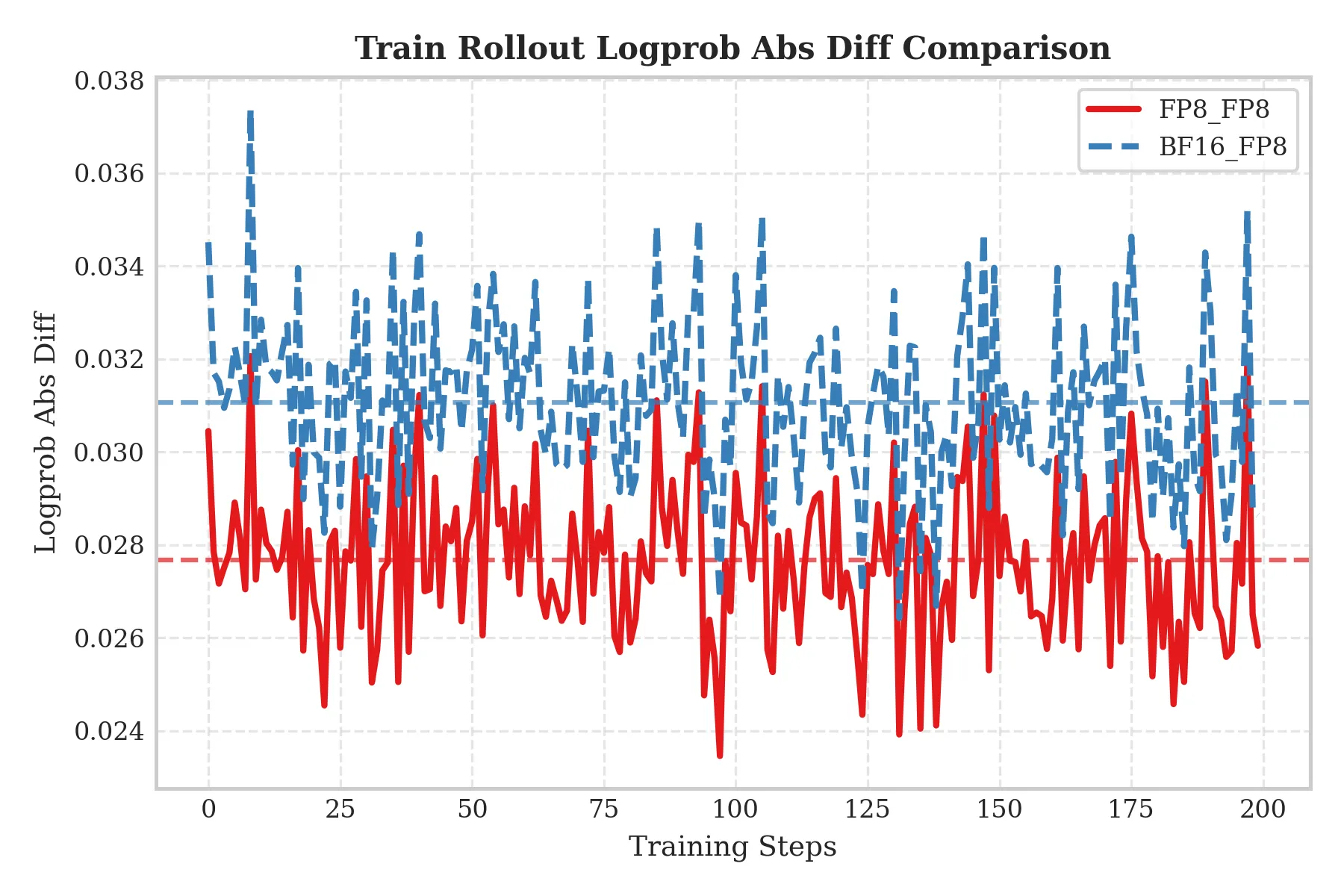

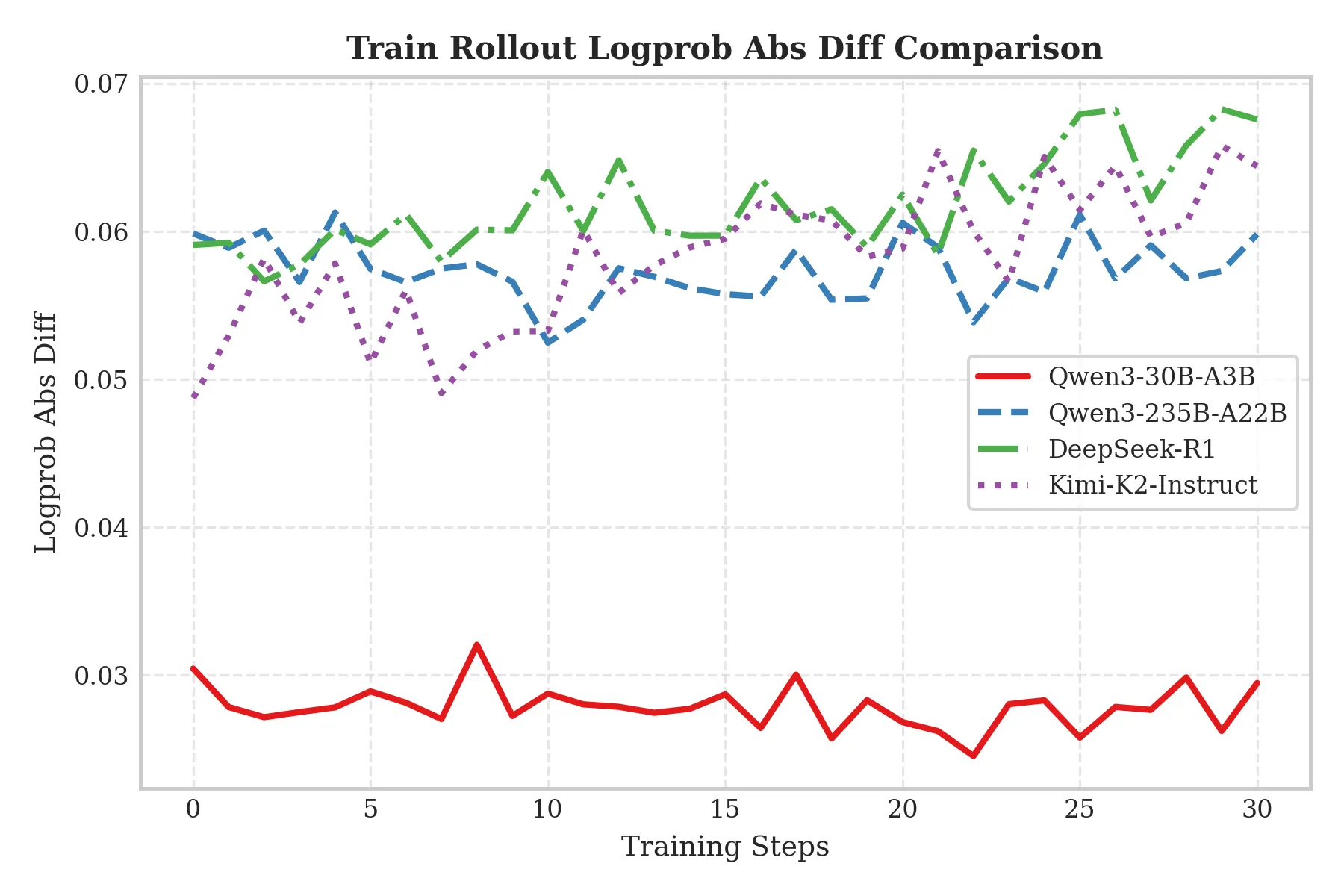

Dense-model experiments demonstrate that FP8-TI effectively suppresses train–inference inconsistency. Building on this, the Ant Group AQ Team extended the study to MoE models in RL to evaluate whether FP8-TI works well for more complex architectures. We find that FP8-TI:

- Reduces TIS clip fraction: Its TIS-clipfrac is significantly lower than that of BF16 Train / FP8 Rollout, meaning fewer clipped updates and higher training stability.

- Narrows the train–rollout log-probability gap: Compared with BF16 Train / FP8 Rollout, this FP8 scheme yields smaller and more stable differences between training and rollout log probabilities.

MoE Experiment Design

To isolate variables for clean comparison, we set up two experimental schemes:

- Case 1 (mixed precision): BF16 training, FP8 rollout.

- Case 2 (unified precision): FP8 training, FP8 rollout.

Key metrics:

- TIS clip fraction (TIS-clipfrac): Measures off-policy training stability; lower is better.

- Absolute difference between train and rollout log probabilities (train_rollout_logprob_abs_diff): Measures how consistent model behavior is between training and rollout; smaller and more stable is better.

MoE Results and Analysis

Qwen3-30B-A3B

- Setup: 2× H20 servers.

On a 30B-scale MoE model, the results clearly show the advantages of FP8-TI:

- Lower TIS-clipfrac: FP8-TI achieves significantly lower TIS-clipfrac than the BF16 Train / FP8 Rollout baseline, indicating fewer clipped updates and more stable training.

- Smaller train–rollout log-probability gap: FP8-TI produces a narrower and more stable range for Train_rollout_logprob_abs_diff, indicating more consistent behavior between training and inference.

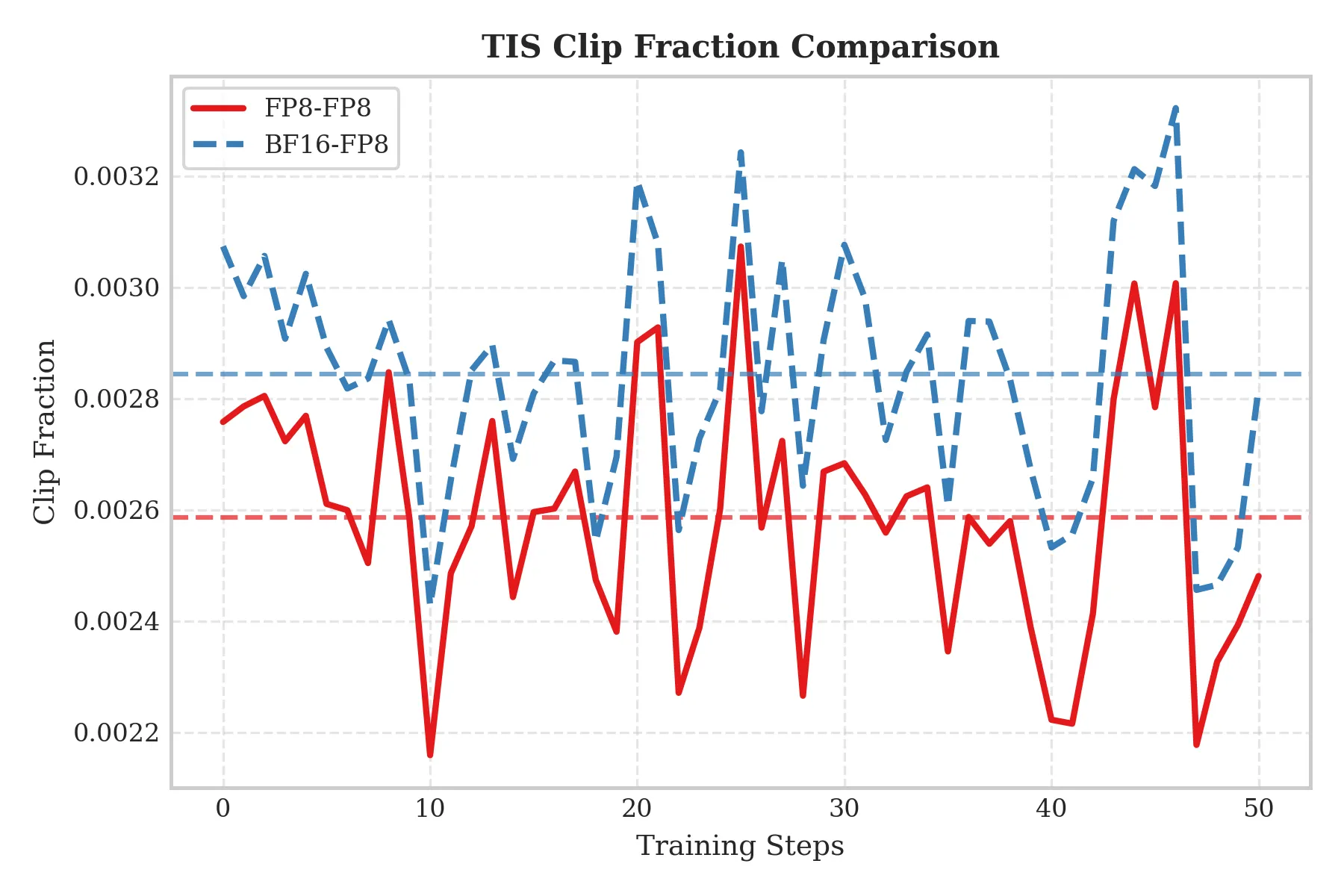

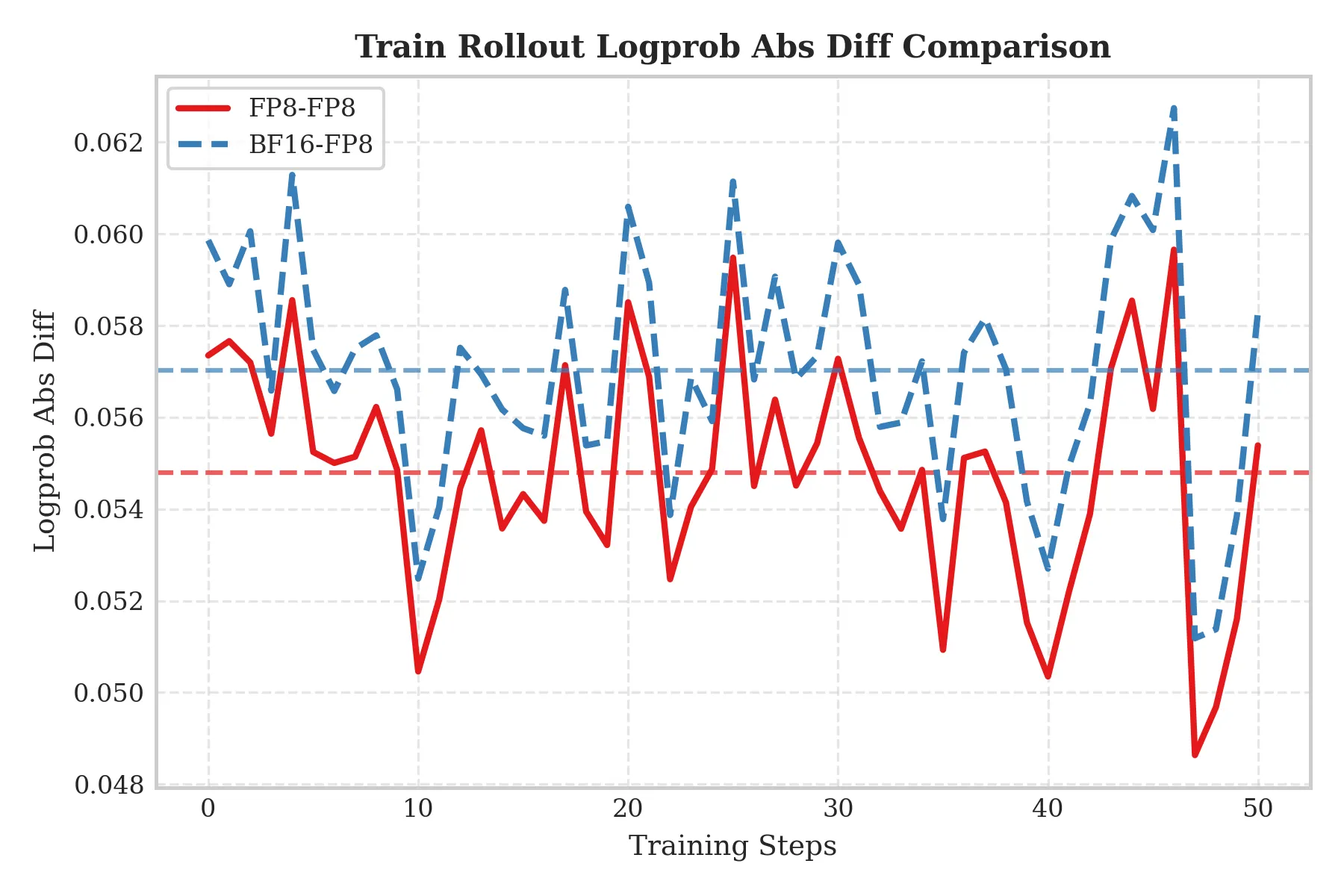

Qwen3-235B-A22B

- Setup: 16× H20 servers.

To evaluate scalability, we replicated the experiments on a 235B-scale model and obtained consistent conclusions:

- Consistent improvements in TIS-clipfrac and train–rollout discrepancy: As shown below, even at 235B scale, FP8-TI continues to reduce TIS-clipfrac and Train_rollout_logprob_abs_diff compared with BF16 Train / FP8 Rollout, demonstrating good scalability.

Conclusion: For MoE RL tasks, using unified FP8 for both training and inference improves training stability and effectively suppresses train–inference inconsistency compared with BF16 Train / FP8 Rollout. This advantage is consistently observed from 30B to 235B MoE models.

Effect of MoE Model Scale on Train–Inference Inconsistency

We further investigate how MoE model size affects train–inference inconsistency under the mixed-precision setting (BF16 Train / FP8 Rollout). Experiments show that as MoE model size increases, train–inference inconsistency becomes more severe.

As shown below, from 30B up to 1T, both TIS-clipfrac and Train_rollout_logprob_abs_diff increase significantly. This suggests that for BF16 Train / FP8 Rollout, larger models tend to suffer more severe train–inference inconsistency, indirectly highlighting the importance of unified-precision schemes such as FP8-TI.

Future Work

Thank you for reading. We see several directions worth further exploration:

- Study train–inference inconsistency more deeply, analyze its root causes, and explore better solutions.

- Investigate quantization strategies more thoroughly, understand how quantization error arises, and design schemes with lower error.

- Improve low-precision training efficiency via better algorithms, frameworks, and hardware–software co-design, hiding the latency of kernel launches and quantization and truly realizing acceleration for both training and inference.

Acknowledgments

- InfiXAI Team: Congkai Xie, Mingfa Feng, Shuo Cai

- Ant Group AQ Team: Yanan Gao, Zhiling Ye, Hansong Xiao

- SGLang RL Team: JiLi, Yefei Chen, Xi Chen, Zilin Zhu

- Miles Team: Chenyang Zhao

- NVIDIA: Juan Yu, NeMo-RL Team